Taft and Mr. Taft is a pitch, a forty-eight-page polite solicitation for money, published in early 1928 to inaugurate the $2,000,000 fund drive on behalf of the Taft School in Watertown, Connecticut. The funds would be used to create a perpetual endowment and to construct Bingham Auditorium (above), the crowning jewel within the buildings that Mr. Taft built or nurtured. The book is also a love letter to Mr. Taft from his Old Boys who wrote it, and the preface frankly states that it was printed without Mr. Taft's prior consent "because he is too modest."

Reading from page two, "Horace Taft's first concern is to know his boys. Once a week during the ripe fall days, a little group of capering lads, at its centre a long-legged figure with a twinkling eye and a magnetic smile, goes out of the School gate and up the road into the country. On a hill by a wood, they build a fire, cook bacon and sausages, eat as only small boys can, and get acquainted."

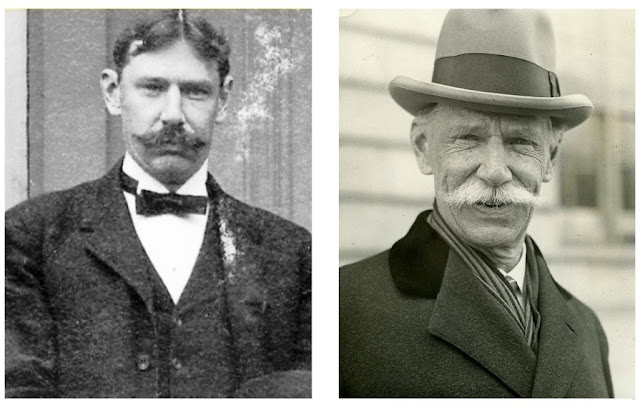

From the same page: "The future is in the hands of the schoolmaster. His fingers, adroit or clumsy, must mold the plastic material of today's boys into the images of tomorrow's men." The image-maker was Horace Dutton Taft, shown below both young and older. Cincinnati-bred and Yale-educated, he stood 6'-4" and was said to be possessed of "the gentlest, brightest blue eyes imaginable."

The story behind Taft and Mr. Taft began on a freezing March Saturday in 1893 when he and his wife took the train up to Watertown from Pelham Manor, New York where his three-year-old preparatory school had outgrown its home. Through a Yale Skull and Bones connection (his father was a founding member), the thirty-two year old Mr. Taft was directed by millionaire shipping magnate F. Curtis Kingsbury to Watertown, where Curtis and Scovill Manufacturing Company head John Buckingham held an interest in a failed summer resort hotel (below, green arrow) which might just become "Mr. Taft's School." Click here for a larger view.

The steep road up to the hotel rose gently from Main Street, back before even turnpikes were paved. The building to the right was built in 1828.

Atop the hill was The Green whose residences included the George Woodruff gingerbread house...

and the home of Alanson Warren.

In the 1840's, a Watertown factory operated by Woodruff, Warren and Nathaniel Wheeler produced a sewing machine which had been invented by a Mister Wilson. Under the name Wheeler and Wilson the firm hit it big, moved to Bridgeport, and eventually became a chief component of Singer.

New boys were captivated by the scale and majesty of the Warren House where everything was as tall as the Headmaster.

Steam radiators such as seen to the left of mandolin boy almost adequately heated 98 boys, 7 masters, Mr. Taft, his wife (the brunette in the back row) and unidentified lady, all viewing a magic lantern show to keep warm.

Not until 1898, five years after occupancy, did Watertown provide electrical power to replace gas jets (such as the one hidden under this mandolin boy's hat) but still the hotel was considered to be a firetrap. Nevertheless in that year Mr. Taft exercised his option to purchase.

In 1900 Mr. Taft wrote his buddy and fellow Schoolmaster Sherman Thacher, "I am now trying an experiment which I am much interested in-- making a rink." Mr. Taft succeeded.

Within a few years, the school had outgrown the Warren House, and in 1908 Mr. Taft constructed a firetrap of his own making, a "temporary" frame cottage across Woodbury Road to house lower school boys, many of whom hitherto were boarded at private residences.

1908 also marked the election of his brother William Howard Taft to the Presidency, and National Magazine interviewed the brother and wife of the President-elect. To enlarge the article, click here.

"My brother, the President." This was taken when Mr. and Mrs. Taft visited the new occupant of the White house,

"The year 1909, which began so gloriously for us with the Inauguration and jollification, ended very sadly. My wife fell ill in the fall and died in December," wrote Horace Taft in his memoirs, thirty-five years later.

"It is the kind of blow that divides a man's life in two. There was nothing to do but throw myself into the work of the school as completely as possible."

The cottage across the road, now known as the Annex, was tripled in size in 1910, and the school grew in another spurt to 116, with twelve Masters.

The original part of the Annex was made over into faculty apartments, and the remainder was occupied for decades by lower mids and eighth graders termed "juniors" until that form was phased out in the 1950's. The massive rear L-wing is shown under construction and across the road, the new Gymnasium was rising as well.

Another view.

A much later photo shows the rear wing of the Annex and behind it, the shallow pond enjoyed by both town and gown for skating in the winter and rafting in the summer.

Concurrent with the construction of the Annex entered a valued helpmate for Mr. Taft in the person of E.C. Eugene Wheeler, shown below in his previous position as Watertown's station master. Until he retired from Taft in 1934, he acted as the school's supervisor of construction much to the relief of Mr. Taft who wrote, "how I wished I'd been regularly taught carpenter work and machinery during summers when I was a boy."

Among Wheeler's undertakings were herding Master Harley Robert's flock of sheep from the station up to the school and attempting to locate the Warren House flagstaff after it was blown off the building by a bolt of lightening. Under his watchful eye, no Taft building burned, and the Warren House and Annex both fell via demolition, in 1929 and 1963, respectively.

There was an exception to the rule, however, when in 1924 the Senior Smoke House burned to the ground. Fortunately for the Seniors who had quite rightly gone into mourning, Mrs. E. H. Scovill had "her portable house" at the ready.

Mr. Taft: "We had planned to build a new school on the top of Nova Scotia Hill giving a splendid outlook over the valley stretching towards Waterbury. I bought three farms (385 acres) but it soon became evident that the expense involved in erecting new buildings and abandoning all of our old plant was beyond our means." Eventually he sold the farms to Scovill "Mac" Buckingham '85, from whose father he had purchased the Warren House, and for years thereafter the Mt. Fair dairy farms produced milk for town and Taft.

Mr. Taft engaged the very top New York City architectural firm of Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson to develop a preliminary scheme for his dream, and they in turn hired the top landscape architect, Olmsted Brothers (out of Boston) led by Frederick Olmsted, Jr., shown below as a preppie at Roxbury Latin.

Calvert Vaux and Olmsted senior had created Central Park, and Fred Jr. followed by creating (among other great works) the all-Tudor planned village of Forest Hills Gardens (NYC) begun in 1908, which remains intact and unaltered to this very day.

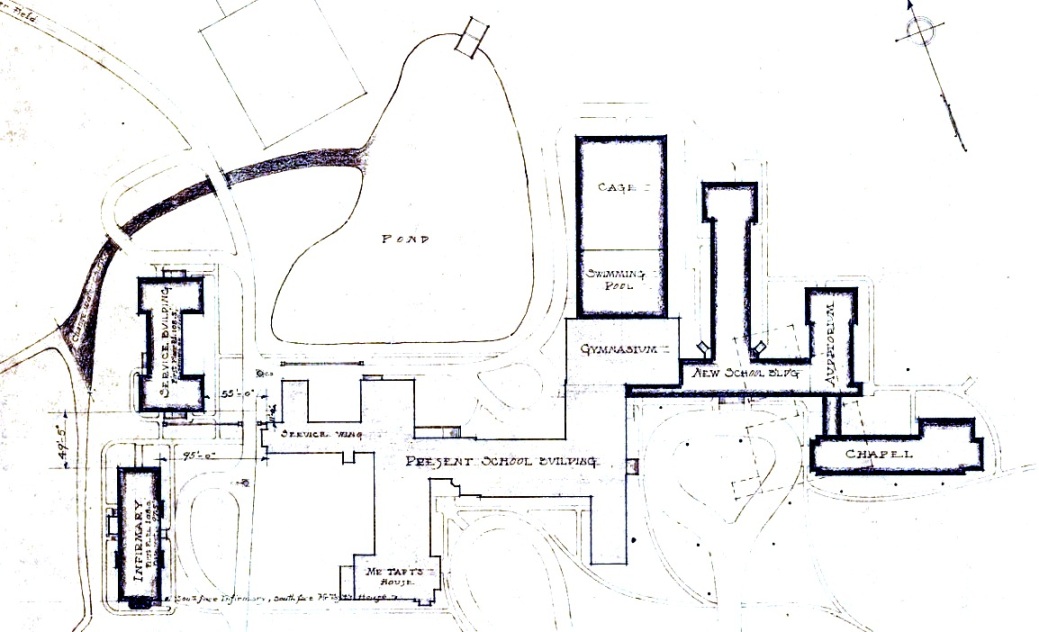

Also in 1908, Goodhue and Olmsted submitted this schematic plan to Taft, a question mark in the future pond indicating the uncertainty of site location. This plan includes a gym containing a stage. To enlarge the plan, click here.

This drawing illustrates architect Goodhue's progress closer to what actually got built. To enlarge, click here.

This property survey, conducted by Wm. B. Reynolds of Waterbury, shows the proposed building in relation to the existing structures.

"This summer we have put the brook that runs though the lot back of the school into a concrete culvert and are going to fill right over it so that when I can afford it, we will have a fine ballfield," wrote Mr. Taft. Invoking a family name, he privately referred to the new structure as "the Hulbert Culvert." The offending now-invisible brook is shown below, top left.

The first permanent and fireproof structure built was the most needed, a proper gymnasium, "and I defy anyone to burn it," Mr. Taft wrote to his friend Sherman Thacher in 1911. "My debt is over $118,000. This year I am going to turn my face the other way and pay off something. Don't you think that a laudable ambition? I'm not proud, but I want to die honest. Sometime I think I'll go ahead and incorporate, but I hate business and I hate incorporation."

This view of the new gymnasium from the opposite side shows the connecting doors for the future main building, to the left of the ventilation air shaft. The wall (and windows) to the right of the shaft would be obscured when the 1931 building was erected.

Until Bingham opened twenty years later, the gymnasium functioned as the school's theatre with a full-scale proscenium stage which could be stored when not in use. The gym was home to the school dances and the school musicians.

In 1912, the loyalty of Mr. Taft's "old boys" was translated into action with the formation of the first association of alumni, so to remove at least one burden from Mr. Taft who hitherto was the association. Under the leadership of Mac Buckingham, this group appeared just as "the King" (as the boys had rechristened Mr. Taft) finally incorporated the school, necessary for the raising of the $300,000 required to build the new school building, to be known as HDT, after Mr. Taft.

"Thanks to my many good friends and especially to my brother Charlie and his wife, we raised the $300,000" in short order, Mr. Taft later recalled. Charlie was Charles Phelps Taft (CPT), the eldest of Mr. Taft's four surviving brothers and the most wealthy by virtue of his marriage to pig iron heiress Anna Sinton. Charlie also edited the Cincinnati Times-Star and owned the Chicago Cubs.

Architect Goodhue's rendering of the new building is accurate with the exception of the presence of a chapel (seen to the far right) which was omitted in the final construction drawings.

The lack of chapel was likely due to reasons economic and not artistic, because God knows nobody could design a church like Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue. Below, his then recently-completed St. Thomas of Fifth Avenue, one of the wonders of the world.

Goodhue had also just completed his only contribution to Princeton, Seventy-seven Hall (now Campbell Hall), so Mr. Taft knew exactly what he was buying.

Construction was commenced in early 1913, and the two-acre HDT would be ready for the fall term with Mr. Taft's house the last-completed in February 1914. From a vantage facing towards the future Bingham Auditorium, a construction shot taken by student William Bourne:

Seen from the same vantage, the (apparently) prefabricated steel trusses for the Study Hall roof are being set in place, and from their curvature would be suspended the clear span barrel vault ceiling of the largest room in the building.

Shown in the spring of 1913, from the opposite vantage, the Study Hall had received its roof.

The Alumni Day Papyrus fairly scintillates with excitement and is the reflection of a tightly run, self-governed, almost secret society which was clearly a subset of Yale. Still, nothing could force sporting news off the front page. (Click here to see the entire issue.)

"We sincerely hope that the Alumni will not cease to regard the 'new' school with the old honor and love, and you will not forget that the spirit of the school remains constant and true," ends the lead article with a photo of the humble beginnings at Pelham, the frozen Mr. Taft at the far right.

"How like a little city, beauty-clad, you stand in ivied loveliness " runs the second verse of the Alma Mater written by John Jessup '24.

The completed building known as HDT was truly fit for "the King" whose three hundred and thirty room private castle it was. If architect Goodhue did not invent this new form that become known as "Collegiate Gothic," he was its master, nevertheless.

Mr. Taft's premiere signature building was more than the sum of its parts, eleven buildings of various shapes and heights combined into a cohesive whole. "Plateaus" indicate short corridors raised above the main corridor to allow for greater ceiling height, in this case, the Dining Hall foyer.

HDT as viewed from the pond (back) side. The towering smokestacks for the bakery and boiler room vied for tallest structure in town with the clock tower. "The numerals are of lead sunk in concrete, and will be covered in gold." The sixth floor room behind the clock would be "a laboratory, the first we have had in the school's history," reads the awe-struck Papyrus, and "around the top of the tower is a series of effigies, among them one said to represent the features of our headmaster."

This view is a continuation to the left of the above, the hotel peeking out. The 1911 gym was seamlessly connected to the new building at the basement and main corridor levels, as if by plan.

And the complete panorama:

A backstage view of the new building, framed entirely in structural steel. The kitchen contained a small refrigeration plant for its "ice box" which led directly onto the service court, so to facilitate the constant deliveries of fresh food from the local farms. On the right can be seen the almost-completed patch to cover the hole through which its boilers had been inserted. The boiler smokestack contained a window, a popular Victorian impossibility.

Looking at HDT from the direction of North Street, the view shows the construction shanty and the storage yard for materiel.

The almost windowless sixth floor "laboratory" contained the electric motor for the clock, mounted high up in the room's center and controlling the four clock faces via wrought-iron linkages which spanned the ceiling. This shot also illustrates the complicated juxtaposition of the four component structures shown.

"The post office is entirely different from anything in the old school," continues the Pap, "and every boy will have his own box and key." The opportunity for boys to race screaming down a nine-story circular iron staircase would also be "extremely different" and right out of Mary Roberts Rinehart.

These two floor plans, published in the school's catalog, are very nearly "as built." All of the rooms along the Main corridor were designated as classrooms, with Mr. Taft occupying the only office in the entire school.

On the second floor of HDT, all the rooms on the left side of the drawing were designated for servants, and the long wing was named Kitchen Corridor, from which a back stair connected directly to the kitchen. After the Service Building was opened in 1927, Kitchen Corridor was converted to boys' rooms.

Some of the classrooms were recitation rooms, with pews instead of desks. The overhead ducts and asbestos-clad steam runs indicate that this is a basement room, probably the one right next to the gym basement. Note the thermostat, ready to slam in those radiators! And to the right of the bookcase is a return air grille.

By far the most imposing and tallest room in the school was Horace Taft's idea of a chapel: the three-story Study Hall, which served to imprison thousands of lowerclassmen over a span of sixty years. HDT was fully-electrified, "and bells, two on each floor, will be rung by automatic clocks." Windows too high to see through eliminated proper day-dreaming, and from his ethereal perch, the all-knowing Master became all-seeing as well.

Having spent twenty-one years in the drafty Warren House, Mr. Taft made certain that he "would never go cold again." This new ingredient was never more evident than in the Study Hall, where, when the temperature dropped to seventy-five, the Johnson pneumatic thermostat would release a loud hiss of air, thus opening the main valve to twenty massive radiators which began clanking their steam hammer aria as they raised the temperature back up to an acceptable eighty. Here the Study Hall wing is shown from the vantage of the (not yet built) Infirmary, with Mr. Taft's house seen to the far right. To see larger views of this and other sections, click here.

Seen from the reverse angle, the Study Hall contained a door in the right corner which connected directly to the living quarters in Mr. Taft's house. The stair ran from the basement to the second floor of his house, thus Mr. Taft was never far away and could sneak up from behind.

Seen from the same vantage, one floor below, the Dining Hall could seat over three hundred at fourteen-top tables, twice the enrollment in 1913. The windows were intentionally inaccessible, because Mr. Taft's passage (which connected his house to the main lobby) ran beneath the windows on the left side and his back yard to the right. Through Mr. Taft's (here obscured) private entrance, servants gained access to his formal dining room.

Seen from the same vantage, one floor below, is the Assembly Room located in the basement in a sort of ventilated dungeon which would serve to accommodate the whole school until Bingham Auditorium opened twenty years later. All the partitions in the building were of terra cotta with plaster finish held in place by metal lath.

The school's motto "To serve and not to be served" carved in stone above the main entry is amusing in the context of a castle with a one to four ratio of servants to boys. The place was run like a New York hotel until 1942 when the manpower shortage led to the creation of the job program, and forever after boys and Masters alike had to make their own beds.

The mouth of "Hulbert's Culvert" shown in the early spring of 1914 and the dry land to the right, before the pond had been created.

Behold the completed pond and properly graded playing fields. "In order to run no chances of lowering the spirit of the school, Mr. Taft is planning to increase the enrollment only by twenty-five boys a year until the maximum number of two-hundred and fifty is reached," purred the Pap.

The 1920 Gun Club posing on the steps of HDT, on the side nearest the Warren House, the future location of CPT.

The nine fireplaces with attendant chimneys provided both literal and symbolic warmth and were dispensed in order of rank. Mr. Taft was given four (counting the one in his office); one for each of the four Master's apartments; and one in the library for the boys.

Boys in the first Library.

The library was a simple affair, but the plaster relief above the fireplace that depicts the tree of knowledge resulted in a tussle between architect Goodhue (not a Yale man) and Mr. Taft. Goodhue had depicted Adam and Eve at the base of the tree, both of whom Mr. Taft summarily ejected from the library, later to become known as the Harley Roberts reception room.

That room bore a passing resemblance to the architect's New York office where Adam and Eve were allowed to flourish.

A desk in a typical boy's room was equipped with a luxurious electric desk lamp and lockable drawers.

As opposed to the spartan dorm rooms, the faculty apartments featured walnut-paneled walls, ornamented ceilings, and plentiful bookcases.

Mr. Taft's second-in-command classics Master Harley Roberts would entertain any willing (or unwilling) audience with his coveted player piano or $3000 Columbia Grafanola, shown here. Following the death of Winnie Taft, Harley became best friend to Horace and was his constant companion, especially in their travels. Among a thousand other accomplishments, Harley selected the school motto and created the golf course.

Mr. Taft's sumptuous residence was a transplanted thirty-room Manhattan townhouse with eight bedrooms, six bathrooms, and a back yard as large as the Study Hall.

Mr. Taft never remarried, but "was tickled" to house a bevy of chaperoning mothers in his seven vacant bedrooms for the thrice-yearly school dances. Here he consults with his Monitors who, because they were his government, he hand-picked regardless of the student voting outcome.

The ivy seemed drawn to Mr. Taft's house.

At that same entry is the King, a 6'-4" person who spent his entire career with persons 4'-6".

Mr. Taft also had long fingers.

A custom bath tub (below) was installed in the White House for his portly brother, so Mr. Taft followed suit with one custom-cast to contain his lengthy frame.

From the rear vantage can be seen the entry to the backyard from the screened porch, and above it is the sleeping porch.

The house did not achieve full occupancy until succeeding Headmaster Paul Cruikshank and his brood took up residence in 1936, photo identification courtesy Sally Cruikshank.

The devil (or the angel) in the detail were the windows of HDT, all operable, with terribly fragile leaded lights.

The hardware was in bronze.

In one stroke, the architecture of the Taft School outstripped all other prep schools. Clockwise from top left, Exeter, Andover, Choate, Loomis, Hotchkiss and Deerfield.

The Warren House would still be required for fifteen more years, with its best rooms converted to faculty apartments. The remainder was given over to servants' quarters and the first school infirmary. "That's the proper idea. If we burn anybody, it ought to be the infirm," quipped Mrs. Charles Phelps Taft. At the highest window can be seen a slender and perilous fire ladder. To the right is the 1911 gymnasium.

Seniors chose to pose in front of the perfect Hemlock in the yard of the old Hotel at "the Senior fence."

By 1918 when this souvenir map was published, Taft (green arrows) had become the chief feature of Watertown. Click here for an HD view, double-click to enlarge.

A close-up view of Taft in its idyllic setting, complete with tear-drop-shaped pond, as originally designed by Olmsted, Jr. Neighboring institutions included Dr. Jackson's Sanatorium, a converted Victorian mansion, later the M'Fingal Inn, its restaurant "only 220 yards from Taft."

Among Wheeler's undertakings were herding Master Harley Robert's flock of sheep from the station up to the school and attempting to locate the Warren House flagstaff after it was blown off the building by a bolt of lightening. Under his watchful eye, no Taft building burned, and the Warren House and Annex both fell via demolition, in 1929 and 1963, respectively.

Mr. Taft: "We had planned to build a new school on the top of Nova Scotia Hill giving a splendid outlook over the valley stretching towards Waterbury. I bought three farms (385 acres) but it soon became evident that the expense involved in erecting new buildings and abandoning all of our old plant was beyond our means." Eventually he sold the farms to Scovill "Mac" Buckingham '85, from whose father he had purchased the Warren House, and for years thereafter the Mt. Fair dairy farms produced milk for town and Taft.

Mr. Taft engaged the very top New York City architectural firm of Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson to develop a preliminary scheme for his dream, and they in turn hired the top landscape architect, Olmsted Brothers (out of Boston) led by Frederick Olmsted, Jr., shown below as a preppie at Roxbury Latin.

Calvert Vaux and Olmsted senior had created Central Park, and Fred Jr. followed by creating (among other great works) the all-Tudor planned village of Forest Hills Gardens (NYC) begun in 1908, which remains intact and unaltered to this very day.

This drawing illustrates architect Goodhue's progress closer to what actually got built. To enlarge, click here.

This property survey, conducted by Wm. B. Reynolds of Waterbury, shows the proposed building in relation to the existing structures.

The first permanent and fireproof structure built was the most needed, a proper gymnasium, "and I defy anyone to burn it," Mr. Taft wrote to his friend Sherman Thacher in 1911. "My debt is over $118,000. This year I am going to turn my face the other way and pay off something. Don't you think that a laudable ambition? I'm not proud, but I want to die honest. Sometime I think I'll go ahead and incorporate, but I hate business and I hate incorporation."

This view of the new gymnasium from the opposite side shows the connecting doors for the future main building, to the left of the ventilation air shaft. The wall (and windows) to the right of the shaft would be obscured when the 1931 building was erected.

Until Bingham opened twenty years later, the gymnasium functioned as the school's theatre with a full-scale proscenium stage which could be stored when not in use. The gym was home to the school dances and the school musicians.

In 1912, the loyalty of Mr. Taft's "old boys" was translated into action with the formation of the first association of alumni, so to remove at least one burden from Mr. Taft who hitherto was the association. Under the leadership of Mac Buckingham, this group appeared just as "the King" (as the boys had rechristened Mr. Taft) finally incorporated the school, necessary for the raising of the $300,000 required to build the new school building, to be known as HDT, after Mr. Taft.

"Thanks to my many good friends and especially to my brother Charlie and his wife, we raised the $300,000" in short order, Mr. Taft later recalled. Charlie was Charles Phelps Taft (CPT), the eldest of Mr. Taft's four surviving brothers and the most wealthy by virtue of his marriage to pig iron heiress Anna Sinton. Charlie also edited the Cincinnati Times-Star and owned the Chicago Cubs.

Architect Goodhue's rendering of the new building is accurate with the exception of the presence of a chapel (seen to the far right) which was omitted in the final construction drawings.

The lack of chapel was likely due to reasons economic and not artistic, because God knows nobody could design a church like Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue. Below, his then recently-completed St. Thomas of Fifth Avenue, one of the wonders of the world.

Goodhue had also just completed his only contribution to Princeton, Seventy-seven Hall (now Campbell Hall), so Mr. Taft knew exactly what he was buying.

Construction was commenced in early 1913, and the two-acre HDT would be ready for the fall term with Mr. Taft's house the last-completed in February 1914. From a vantage facing towards the future Bingham Auditorium, a construction shot taken by student William Bourne:

Seen from the same vantage, the (apparently) prefabricated steel trusses for the Study Hall roof are being set in place, and from their curvature would be suspended the clear span barrel vault ceiling of the largest room in the building.

Shown in the spring of 1913, from the opposite vantage, the Study Hall had received its roof.

The Alumni Day Papyrus fairly scintillates with excitement and is the reflection of a tightly run, self-governed, almost secret society which was clearly a subset of Yale. Still, nothing could force sporting news off the front page. (Click here to see the entire issue.)

"We sincerely hope that the Alumni will not cease to regard the 'new' school with the old honor and love, and you will not forget that the spirit of the school remains constant and true," ends the lead article with a photo of the humble beginnings at Pelham, the frozen Mr. Taft at the far right.

"How like a little city, beauty-clad, you stand in ivied loveliness " runs the second verse of the Alma Mater written by John Jessup '24.

The completed building known as HDT was truly fit for "the King" whose three hundred and thirty room private castle it was. If architect Goodhue did not invent this new form that become known as "Collegiate Gothic," he was its master, nevertheless.

Mr. Taft's premiere signature building was more than the sum of its parts, eleven buildings of various shapes and heights combined into a cohesive whole. "Plateaus" indicate short corridors raised above the main corridor to allow for greater ceiling height, in this case, the Dining Hall foyer.

This view is a continuation to the left of the above, the hotel peeking out. The 1911 gym was seamlessly connected to the new building at the basement and main corridor levels, as if by plan.

A backstage view of the new building, framed entirely in structural steel. The kitchen contained a small refrigeration plant for its "ice box" which led directly onto the service court, so to facilitate the constant deliveries of fresh food from the local farms. On the right can be seen the almost-completed patch to cover the hole through which its boilers had been inserted. The boiler smokestack contained a window, a popular Victorian impossibility.

Looking at HDT from the direction of North Street, the view shows the construction shanty and the storage yard for materiel.

The almost windowless sixth floor "laboratory" contained the electric motor for the clock, mounted high up in the room's center and controlling the four clock faces via wrought-iron linkages which spanned the ceiling. This shot also illustrates the complicated juxtaposition of the four component structures shown.

"The post office is entirely different from anything in the old school," continues the Pap, "and every boy will have his own box and key." The opportunity for boys to race screaming down a nine-story circular iron staircase would also be "extremely different" and right out of Mary Roberts Rinehart.

Some of the classrooms were recitation rooms, with pews instead of desks. The overhead ducts and asbestos-clad steam runs indicate that this is a basement room, probably the one right next to the gym basement. Note the thermostat, ready to slam in those radiators! And to the right of the bookcase is a return air grille.

By far the most imposing and tallest room in the school was Horace Taft's idea of a chapel: the three-story Study Hall, which served to imprison thousands of lowerclassmen over a span of sixty years. HDT was fully-electrified, "and bells, two on each floor, will be rung by automatic clocks." Windows too high to see through eliminated proper day-dreaming, and from his ethereal perch, the all-knowing Master became all-seeing as well.

Having spent twenty-one years in the drafty Warren House, Mr. Taft made certain that he "would never go cold again." This new ingredient was never more evident than in the Study Hall, where, when the temperature dropped to seventy-five, the Johnson pneumatic thermostat would release a loud hiss of air, thus opening the main valve to twenty massive radiators which began clanking their steam hammer aria as they raised the temperature back up to an acceptable eighty. Here the Study Hall wing is shown from the vantage of the (not yet built) Infirmary, with Mr. Taft's house seen to the far right. To see larger views of this and other sections, click here.

Seen from the reverse angle, the Study Hall contained a door in the right corner which connected directly to the living quarters in Mr. Taft's house. The stair ran from the basement to the second floor of his house, thus Mr. Taft was never far away and could sneak up from behind.

Seen from the same vantage, one floor below, the Dining Hall could seat over three hundred at fourteen-top tables, twice the enrollment in 1913. The windows were intentionally inaccessible, because Mr. Taft's passage (which connected his house to the main lobby) ran beneath the windows on the left side and his back yard to the right. Through Mr. Taft's (here obscured) private entrance, servants gained access to his formal dining room.

Seen from the same vantage, one floor below, is the Assembly Room located in the basement in a sort of ventilated dungeon which would serve to accommodate the whole school until Bingham Auditorium opened twenty years later. All the partitions in the building were of terra cotta with plaster finish held in place by metal lath.

The school's motto "To serve and not to be served" carved in stone above the main entry is amusing in the context of a castle with a one to four ratio of servants to boys. The place was run like a New York hotel until 1942 when the manpower shortage led to the creation of the job program, and forever after boys and Masters alike had to make their own beds.

The mouth of "Hulbert's Culvert" shown in the early spring of 1914 and the dry land to the right, before the pond had been created.

The 1920 Gun Club posing on the steps of HDT, on the side nearest the Warren House, the future location of CPT.

The nine fireplaces with attendant chimneys provided both literal and symbolic warmth and were dispensed in order of rank. Mr. Taft was given four (counting the one in his office); one for each of the four Master's apartments; and one in the library for the boys.

The library was a simple affair, but the plaster relief above the fireplace that depicts the tree of knowledge resulted in a tussle between architect Goodhue (not a Yale man) and Mr. Taft. Goodhue had depicted Adam and Eve at the base of the tree, both of whom Mr. Taft summarily ejected from the library, later to become known as the Harley Roberts reception room.

That room bore a passing resemblance to the architect's New York office where Adam and Eve were allowed to flourish.

A desk in a typical boy's room was equipped with a luxurious electric desk lamp and lockable drawers.

As opposed to the spartan dorm rooms, the faculty apartments featured walnut-paneled walls, ornamented ceilings, and plentiful bookcases.

Mr. Taft never remarried, but "was tickled" to house a bevy of chaperoning mothers in his seven vacant bedrooms for the thrice-yearly school dances. Here he consults with his Monitors who, because they were his government, he hand-picked regardless of the student voting outcome.

The ivy seemed drawn to Mr. Taft's house.

A custom bath tub (below) was installed in the White House for his portly brother, so Mr. Taft followed suit with one custom-cast to contain his lengthy frame.

From the rear vantage can be seen the entry to the backyard from the screened porch, and above it is the sleeping porch.

The house did not achieve full occupancy until succeeding Headmaster Paul Cruikshank and his brood took up residence in 1936, photo identification courtesy Sally Cruikshank.

The hardware was in bronze.

In one stroke, the architecture of the Taft School outstripped all other prep schools. Clockwise from top left, Exeter, Andover, Choate, Loomis, Hotchkiss and Deerfield.

Seniors chose to pose in front of the perfect Hemlock in the yard of the old Hotel at "the Senior fence."

By 1918 when this souvenir map was published, Taft (green arrows) had become the chief feature of Watertown. Click here for an HD view, double-click to enlarge.

A close-up view of Taft in its idyllic setting, complete with tear-drop-shaped pond, as originally designed by Olmsted, Jr. Neighboring institutions included Dr. Jackson's Sanatorium, a converted Victorian mansion, later the M'Fingal Inn, its restaurant "only 220 yards from Taft."

Interesting view of Warren House, showing rear wing and back buildings, from 1918 map.

To see a condensation of the 1920 Taft Annual, click here.

That auspicious event opened the door for a second fundraising campaign, for the school had now outgrown HDT. Heeding the advice of Hotchkiss Headmaster Buehler, Mr. Taft engaged a newfangled professional fundraising expert, and key to the plan was the conversion of the school into a non-profit entity, which Mr. Taft accomplished by giving the school to the Alumni. In April of 1927 the plan (and solicitation) was heralded in the Watertown News:

The work would be phased as money allowed:

Because HDT architect Goodhue had passed away in 1924, James Gamble Rogers, another esteemed New York designer and (this time) a Yale man was chosen to conceive the Upper School, which included a proper auditorium, and once again the scheme included a chapel. Click here for an enlarged view.

But Rogers was best-known for Yale's Harkness Memorial Quadrangle (1917) . Rogers was Yale classmate of and pet architect to Edward Harkness who would become the largest contributor to Taft's campaign.

The first phase of the work included both the Infirmary and the Service Building. "We have, in our judgement, a ripping board of trustees," Mr. Taft wrote Sherman Thacher in July, 1927. "They passed a vote authorizing me to sign a contract for the first two buildings in our program, and the bid is $360,000."

Another plan view includes the chapel, a swimming pool, and "a cage," none of which got built.

A preliminary plan from 1925 displays a completely different scheme, where both the chapel and the upper school building are free-standing. Note also the isolation wing behind the infirmary.

To ensure complete success of the campaign, the experts nudged modest Mr. Taft to play his ace, and the November 1927 announcement in the New York Times carried the endorsement of none other than Chief Justice William Howard Taft. But the best thing of all was that the experts had gotten "The Taft School" into the New York Times.

In February of 1928, the now-friendly New York Times announced very welcome news: the receipt from Edward Harkness of a half million dollars, which would be entirely applied towards the new endowment, about which Mr. Taft had written Sherman Thacher. "I should like very much to have a big fund to enable me to have a sliding scale of tuition charges, so that without calling them 'scholarship boys,' I might admit a goodly number of the sons of lawyers and doctors and professional men generally, for a greatly reduced sum."

Mr. Taft's brother Charlie, who had already contributed heavily to the HDT campaign, ponied up another $300,000 to enable construction to begin. By early 1928, both the Infirmary and the Service Building were well underway.

The Infirmary was designed to accommodate forty boys in double rooms, at a bare minimum. Half of the boys had been quarantined when the unspeakable influenza epidemic hit the school in 1918, killing both a boy and Master, and cases of tonsillitis, whooping cough, pneumonia, scarlet fever, mumps, measles, polio, and near-fatal sporting injuries were not uncommon. In 1920, for example, diphtheria broke out, and the school took an emergency spring break six weeks ahead of schedule.

A construction elevation with two fewer two chimneys.

"The School Infirmary, a new, separate four-storied building has recently been completed," read the school's catalog. "It is a fully equipped hospital in every detail, with an isolation ward for contagious diseases, diet kitchens, operating room, and solarium." The near side entrance was for boys, the front door for hopeful visitors.

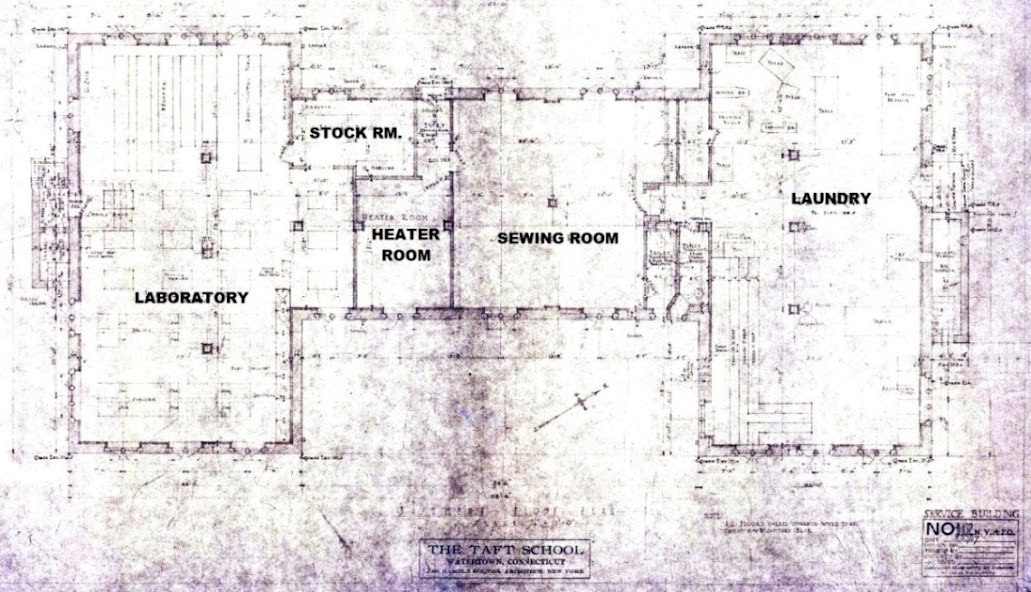

The fact that the building had no visible means of entry gave the Service Building an air of mystery, and immediately upon completion the boys renamed it "The Wombatorium" after its furtive inhabitants. The only entries were discretely concealed side stairs.

The right side of the basement was given over to a full-service school laundry (necessitating another retinue of servants), and the left side allowed for the first proper science laboratory.

The removal of the laboratory from the seventh floor of HDT likely resulted in a collective sigh of relief, for now only servants could not be immediately evacuated.

To ensure the privacy of Mr. Taft's house, this landscape scheme developed by the Olmsted Brothers included an enclosed garden in his back yard.

This scheme had been on the drawing boards since 1923.

Mr. Taft had better things to do than to squander money on himself. Here is his messy yard in 1923, showing also the back part of the HDT bakery oven (left) and the elevated dining room windows (right).

A pre-garden view, the Infirmary in the foreground.

With the completion of the Infirmary and Service Building, the now-empty Warren House could give way for the construction of the Upper School Building which would be named CPT, for Charlie Taft.

Unwilling to begin construction sans cash in hand, at age 67 Mr. Taft embarked upon a year-long nation-wide series of personal appearances to greet his old boys. Writing to his treasured secretary Minerva Bovaird in May, 1928, he said, "Last week I went west, speaking at dinners at Cincinnati, Chicago, Detroit and Cleveland. Last night I spoke at Washington and I bored a small company here tonight (Philadelphia.) We shall see a million and a half, but I am not very hopeful of going beyond that." But by the end of November, he had raised a million and three-quarters. (New York Times)

To his small but fiercely loyal Alumni Association this shortfall was simply unacceptable, so just in time for Christmas they released this plaintive mass mailer, signed by forty-four old boys.

It took four months more, but by April of 1929 the goal was attained, and work could finally begin on this "splendid fireproof structure." Mr. Taft wrote Sherman Thacher: "Yes, we have gone over the top. We need a million or two more, but at any rate we have got the amount that we dared ask for. P.S.-- Can you tell a man that his boy is no good without hurting his feelings?"

Remarkably and against all known odds, Architect Rogers set aside his own style of design in favor of Goodhue's, "and not even the experienced eye could say where the old building left off and the new building began." James McWalters, the builder credited here, was also responsible for the Manhattan residences of Vincent Astor and FDR's mother.

The ornamental cupola (top left) is a fire vent equipped with windows which open by gravity when "the rope is cut." Nestled between the setback buttresses is the gothic scenery door, and the small building to the right of the stage house contains the stage-level property room and dressing rooms on the upper floor.

Yale made the mistake of hiring an architect other than Rogers to design its 1926 theatre, far less attractive than Bingham and resembling an uninspired first draft.

This long shot of the completed Taft campus shows all the buildings, old and new, as if designed by a singular architect. This photo was taken before the new gym (1955) forever obscured architect Roger's best windows, those in Graduation Courtyard.

A more majestic vantage is seen from the eleventh fairway. Taft may have lacked a swimming pool, but the majority of the ninety acre campus was a golf course. The near nine holes had been laid out by Harley Roberts in 1898, and shortly after CPT opened, the course was doubled in size.

To view a two minute color film of Mr. Taft's Buildings, click here.

A CPT tower room with bay window.

This diagrammatic plan better explains CPT, which connected (bottom left) to HDT, but only at the basement and Main Corridor levels.

"Walking from the single-story HDT main corridor, one is led down a series of steps until the ceilings become not only double-height, but vaulted." The left archway leads to the CPT main lobby, the right leads down to the library.

This half-way vestibule contains the second-best set of Roger's windows, which face the road. The open door leads to the Library.

The Library was a haven for posed photographs.

That room contained nothing (beside the books) but fine finishes and fine furnishings.

Further down the corridor was the Common Room which, with ceiling high paneling, bested the Library. "The Common Room at Taft," wrote the Watertown News, "is more than just four walls. It radiates the beaming personality of its genial founder, Horace Taft yclept the 'King.'" At the opposite end was a raised stage complete with grand piano.

The CPT classrooms were half-again the height of those in HDT and fully-windowed.

The individual responsible for the good taste on display was the dapper Master of English and Dramatics Coach Rollo DeWilton. Years later, as assistant editor-in-chief at MacMillan, he made possible the publication of Mr. Taft's autobiography, which de Wilton had begged him to write.

Between the man pictured above and architect Rogers, nothing took precedence above fixing the details of the $200,000+ auditorium, whose completion lagged six month behind the rest of the building which had cost a mere $300,000. When this miniature Broadway playhouse was finally opened in February, 1931, it was named after its principal donors, Standard Oil heirs Harry Bingham '06 and his sister Elizabeth, both of Cleveland and Palm Beach. The gate guarding the foyer to Bingham Auditorium was straight out of a boy's idea of an actual castle.

Bingham was the most beautiful of all school auditoriums and was completely equipped. With five-hundred and twenty-seven seats, it could accommodate not only the boys and their Masters, but everyone else as well.

Oak paneling and wine-colored mohair seat fabric combined to make a plush and inviting room, as shown in this 1970 photograph. The five pairs of entry doors were upholstered in hand-tooled leather, tacked down with brass nails.

This contemporary shot illustrates Bingham's alignment upon the center axis of the building: out the middle doors can be seen a straight shot all the way back to HDT. Music practice rooms lined the basement of the auditorium, and beneath the stage was a carpenter shop and trap room.

The stage itself was a full-scale erector set as specified by consulting engineer Clyde R. Place who a year later would do the same for Radio City Music Hall, specifying the same top-notch vendors. The boy center is holding the omnipresent Vespers lectern, custom-tailored to match the room, in this 1950's view of the stage.

John Godfrey "JG" Taft '72, the nineteenth Taft descendant, at the controls of the Westinghouse stage switchboard.

An early and lavish de Wilton stage production was A. A. Milnes' "The Perfect Alibi," and its setting looked exactly like the new faculty apartments.

To give one an idea of the scale, only three of the six CPT faculty apartments could fit into the rear wing, shown here.

All six had been designed by Rollo DeWilton to accommodate royalty, so not surprisingly the first two tenants of the second floor were Harley Roberts and Rollo DeWilton. Harley was given the rear wing apartment, with seven rooms and two baths, and Rollo had to make do with six and one. Posed below is Master Jack Reardon in the third best lair, way up on the third floor.

The same Horace Taft who was one of the nation's most outspoken supporters of Prohibiton nevertheless allowed the installation of secret closets to secure the stash in event of raid. Privately, he considered Prohibition to be almost as stupid as Reconstruction.

The physical plant, now quadrupled in size, required constant top dollar upkeep, and this care was giving by the Hannings, father and son who covered the job for seventy-five years, with Jimmy Sr. (seated) putting in fifty-nine before he died on the job.

One of the Hanning duties was control of the Master Keys, shown below, Sargent and Russwin. Not surprisingly, the heirs to both hardware fortunes graduated from Taft.

That key would be necessary for certain bad boys to prowl the Taft steam tunnels, large enough to crawl through, which connected the Steam House to CPT (right) and replaced the abandoned boilers in HDT (left) which also fed the Infirmary and the Service Building.

Nothing could conceal the hundred foot Art Deco steeple of the Steam House, located as far away from the main buildings as possible to minimize the now long-forgotten pestilence of coal dust. The massive high-pressure boilers pumped out steam sufficient to heat, on the coldest night of the year, a room with its windows thrown wide open.

Mr. Taft's jubilation over the new buildings would be overshadowed when many of his fund-raising pledges were rendered worthless by the crash of October 29, 1929. Variety was the only newspaper brash enough to spell it out, in words of four letters or less.

"Payments were prompt and were willingly made till the depression struck us," wrote Mr. Taft, "when two hundred thousand remained unpaid, and the building expense beyond the two million made a much more substantial debt than we expected, and the depression did not help us in paying it." It wasn't paid off for another twenty years, long after Mr. Taft's retirement, by his successor Paul Cruikshank (left).

In the two years following the crash, Mr. Taft also suffered the deaths of his brothers Will and Charlie, Charlie's wife, his lifelong friend Sherman Thacher, and his aide-de-camp Harley Roberts. Harley's death was the most wrenching, because he collapsed in the school Dining Hall and died that night in his new apartment. "The long corridors of the school, generally ringing with the unrestrained, exuberant laughter of carefree youth, were reverently hushed this morning, and the boys gathered in their class rooms in awe and silence," wrote the Waterbury paper.

As the depression dragged on, no one wanted Mr. Taft to retire more than Mr. Taft himself, but he felt it was his duty to pay his debts "and die an honest man." 'Twas not to be, however, and Mr. Taft handed over the reins at the end of 1936. Following a year of travel, he returned home and took up residence in the gingerbread house that faced the school.

With the new headmaster's blessing, Mr. Taft taught a senior civics class at the school until his death, eight years later.

This diagrammatic plan better explains CPT, which connected (bottom left) to HDT, but only at the basement and Main Corridor levels.

"Walking from the single-story HDT main corridor, one is led down a series of steps until the ceilings become not only double-height, but vaulted." The left archway leads to the CPT main lobby, the right leads down to the library.

This half-way vestibule contains the second-best set of Roger's windows, which face the road. The open door leads to the Library.

The Library was a haven for posed photographs.

Further down the corridor was the Common Room which, with ceiling high paneling, bested the Library. "The Common Room at Taft," wrote the Watertown News, "is more than just four walls. It radiates the beaming personality of its genial founder, Horace Taft yclept the 'King.'" At the opposite end was a raised stage complete with grand piano.

The CPT classrooms were half-again the height of those in HDT and fully-windowed.

The individual responsible for the good taste on display was the dapper Master of English and Dramatics Coach Rollo DeWilton. Years later, as assistant editor-in-chief at MacMillan, he made possible the publication of Mr. Taft's autobiography, which de Wilton had begged him to write.

Between the man pictured above and architect Rogers, nothing took precedence above fixing the details of the $200,000+ auditorium, whose completion lagged six month behind the rest of the building which had cost a mere $300,000. When this miniature Broadway playhouse was finally opened in February, 1931, it was named after its principal donors, Standard Oil heirs Harry Bingham '06 and his sister Elizabeth, both of Cleveland and Palm Beach. The gate guarding the foyer to Bingham Auditorium was straight out of a boy's idea of an actual castle.

Oak paneling and wine-colored mohair seat fabric combined to make a plush and inviting room, as shown in this 1970 photograph. The five pairs of entry doors were upholstered in hand-tooled leather, tacked down with brass nails.

This contemporary shot illustrates Bingham's alignment upon the center axis of the building: out the middle doors can be seen a straight shot all the way back to HDT. Music practice rooms lined the basement of the auditorium, and beneath the stage was a carpenter shop and trap room.

The stage itself was a full-scale erector set as specified by consulting engineer Clyde R. Place who a year later would do the same for Radio City Music Hall, specifying the same top-notch vendors. The boy center is holding the omnipresent Vespers lectern, custom-tailored to match the room, in this 1950's view of the stage.

John Godfrey "JG" Taft '72, the nineteenth Taft descendant, at the controls of the Westinghouse stage switchboard.

An early and lavish de Wilton stage production was A. A. Milnes' "The Perfect Alibi," and its setting looked exactly like the new faculty apartments.

To give one an idea of the scale, only three of the six CPT faculty apartments could fit into the rear wing, shown here.

All six had been designed by Rollo DeWilton to accommodate royalty, so not surprisingly the first two tenants of the second floor were Harley Roberts and Rollo DeWilton. Harley was given the rear wing apartment, with seven rooms and two baths, and Rollo had to make do with six and one. Posed below is Master Jack Reardon in the third best lair, way up on the third floor.

The same Horace Taft who was one of the nation's most outspoken supporters of Prohibiton nevertheless allowed the installation of secret closets to secure the stash in event of raid. Privately, he considered Prohibition to be almost as stupid as Reconstruction.

In the two years following the crash, Mr. Taft also suffered the deaths of his brothers Will and Charlie, Charlie's wife, his lifelong friend Sherman Thacher, and his aide-de-camp Harley Roberts. Harley's death was the most wrenching, because he collapsed in the school Dining Hall and died that night in his new apartment. "The long corridors of the school, generally ringing with the unrestrained, exuberant laughter of carefree youth, were reverently hushed this morning, and the boys gathered in their class rooms in awe and silence," wrote the Waterbury paper.

As the depression dragged on, no one wanted Mr. Taft to retire more than Mr. Taft himself, but he felt it was his duty to pay his debts "and die an honest man." 'Twas not to be, however, and Mr. Taft handed over the reins at the end of 1936. Following a year of travel, he returned home and took up residence in the gingerbread house that faced the school.

With the new headmaster's blessing, Mr. Taft taught a senior civics class at the school until his death, eight years later.

The year before his death, Mr. Taft's memoirs were published, the work of a man who was amused to be thought of as "a superannuated pedagogue." To read his book, click here.

Through the miracle of talking pictures, Mr. Taft can be seen and heard delivering to his old boys a greeting, excerpted here. "The lines have fallen to me in pleasant places" he quotes from Psalms 16.

Upon the occasion of Mr. Taft's retirement (at age seventy-five), the Waterbury paper wrote: "At Taft, education and mass-production are incompatible terms: Taft turns out a bench-made product." Likewise Mr. Taft's buildings were bench-made and maintain a dignity to which new buildings can only aspire.

Dedicated to the memory of Mister Cobb.

About the author

Since his days on the Taft stage, Mr. Foreman has spent his life restoring and operating fine historic theatres, and now he writes about them.

Photo Credits

Blake Joblin

The Taft School

Charles Crowell

Olmsted Brothers

Yale special collections

RAMSA

Acknowledgments

Through the miracle of talking pictures, Mr. Taft can be seen and heard delivering to his old boys a greeting, excerpted here. "The lines have fallen to me in pleasant places" he quotes from Psalms 16.

Upon the occasion of Mr. Taft's retirement (at age seventy-five), the Waterbury paper wrote: "At Taft, education and mass-production are incompatible terms: Taft turns out a bench-made product." Likewise Mr. Taft's buildings were bench-made and maintain a dignity to which new buildings can only aspire.

###

For an index of other Taft School articles, click here.Dedicated to the memory of Mister Cobb.

About the author

Since his days on the Taft stage, Mr. Foreman has spent his life restoring and operating fine historic theatres, and now he writes about them.

Blake Joblin

The Taft School

Charles Crowell

Olmsted Brothers

Yale special collections

RAMSA

Acknowledgments

Joe Booth, architect

Beth Lovallo, Taft School archivist

Julie Reiff, former Bulletin editor

Alison Gilchrist, former archivist

Harry Stearns, former archivist

Casey Long, Agnes Scott library

Jessica Dooling, Yale Library Manuscripts and Archives

Thanks also to Brad Joblin, Tom Strumolo, Garry Motter, Rick Zimmerman, Ralph Schusler, Dick Cobb, Scott Allison and Sally Cruikshank.

Books

Taft, Horace Dutton, "Memories and Opinions," 1942

Anthony, Carl, "Nellie Taft," 2006

Bowen, Roger, "Frank Boyden: Dean of the Headmasters," 1968

Chase,Thurston, "Eaglebrook: The First 50 Years," 1972

Julie Reiff, former Bulletin editor

Alison Gilchrist, former archivist

Harry Stearns, former archivist

Casey Long, Agnes Scott library

Jessica Dooling, Yale Library Manuscripts and Archives

Thanks also to Brad Joblin, Tom Strumolo, Garry Motter, Rick Zimmerman, Ralph Schusler, Dick Cobb, Scott Allison and Sally Cruikshank.

Books

Taft, Horace Dutton, "Memories and Opinions," 1942

Anthony, Carl, "Nellie Taft," 2006

Bowen, Roger, "Frank Boyden: Dean of the Headmasters," 1968

Chase,Thurston, "Eaglebrook: The First 50 Years," 1972

Crowell, Florence, "Watertown," 2002

Dallas, John T., "Harley Fish Roberts of the Taft School," 1930

Dallas, John T., "Mr. Taft," 1949

Katz, Sandra L., "Dearest of Geniuses" [Theodate Pope Riddle], 2013

Klaus, Susan L., "A Modern Arcadia" [Forest Hills Gardens], 2002

Lovelace, Richard H., "Mr. Taft's School," 1990

Lovelace, Richard H., "Taft: 75 Years in Pictures," 1965

Nicholson, William G. (editor), "The Taft-Thacher Letters," 1985

Nicholson, William G., "Those Who Served," 1989

Place, Clyde R,. "Specifications for Taft Upper School," 1930

Romano, Anne, "Winnie Taft," 1997

Saltonstall, William G., "Lewis Perry of Exeter: a Gentle Memoir," 1980

Spykman, E.C., "Westover," 1959

Taft School, "Taft and Mr. Taft," 1928

Articles

Taft, Horace Dutton, "Half a Century at the Taft School," 1940 December, The Lure of the Litchfield Hills

Life Magazine, "The Tafts of Cincinnati," May 26, 1952

Mannering, Mitchell, "A Day at the Taft School," 1909 February, National Magazine

McCawley, Janet Cruikshank, "View from the Third Floor," 1999 Spring, Taft Alumni Bulletin

Taft, Robert, Jr., "Au Revoir, Mes Amis," 1980

Periodicals

Taft school Alumni Bulletin, 1963-current

Taft School Annual, 1943-1973

Taft School Catalog, 1937

Taft School Catalog, 1972

Taft School Papyrus, 1913-1931

Interviews or correspondence

Masters

John Esty

Rollo DeWilton

Joe Cunningham

Dick Cobb

Frank Strasburger

Students

Jim Morrison '43

R.L. Foreman, Jr. '44

Rawson Foreman '58

Rick Davis '59

Fran Moore '68

Jeff Boak '70

John Bell '70

Faculty Brats

Sally Cruikshank

Mary Currie

Debbie Carroll

Staff

Jim Hanning, Superintendent

John McVerry, School Carpenter

Internet sites

New York Times archive

Watertown Historical Society

The History of the Taft Building [New Haven Taft Hotel]

http://politicalstrangenames.blogspot.com/2017/09/ [Buckinghams]

University of Cincinnati, "The Taft Influence"

The Taft School "Timeline"

Agnes Scott College

Olmsted Brothers

Dallas, John T., "Harley Fish Roberts of the Taft School," 1930

Dallas, John T., "Mr. Taft," 1949

Katz, Sandra L., "Dearest of Geniuses" [Theodate Pope Riddle], 2013

Klaus, Susan L., "A Modern Arcadia" [Forest Hills Gardens], 2002

Lovelace, Richard H., "Mr. Taft's School," 1990

Lovelace, Richard H., "Taft: 75 Years in Pictures," 1965

Nicholson, William G. (editor), "The Taft-Thacher Letters," 1985

Nicholson, William G., "Those Who Served," 1989

Place, Clyde R,. "Specifications for Taft Upper School," 1930

Romano, Anne, "Winnie Taft," 1997

Saltonstall, William G., "Lewis Perry of Exeter: a Gentle Memoir," 1980

Spykman, E.C., "Westover," 1959

Taft School, "Taft and Mr. Taft," 1928

Articles

Taft, Horace Dutton, "Half a Century at the Taft School," 1940 December, The Lure of the Litchfield Hills

Life Magazine, "The Tafts of Cincinnati," May 26, 1952

Mannering, Mitchell, "A Day at the Taft School," 1909 February, National Magazine

McCawley, Janet Cruikshank, "View from the Third Floor," 1999 Spring, Taft Alumni Bulletin

Taft, Robert, Jr., "Au Revoir, Mes Amis," 1980

Periodicals

Taft school Alumni Bulletin, 1963-current

Taft School Annual, 1943-1973

Taft School Catalog, 1937

Taft School Catalog, 1972

Taft School Papyrus, 1913-1931

Interviews or correspondence

Masters

John Esty

Rollo DeWilton

Joe Cunningham

Dick Cobb

Frank Strasburger

Students

Jim Morrison '43

R.L. Foreman, Jr. '44

Rawson Foreman '58

Rick Davis '59

Fran Moore '68

Jeff Boak '70

John Bell '70

Faculty Brats

Sally Cruikshank

Mary Currie

Debbie Carroll

Staff

Jim Hanning, Superintendent

John McVerry, School Carpenter

Internet sites

New York Times archive

Watertown Historical Society

The History of the Taft Building [New Haven Taft Hotel]

http://politicalstrangenames.blogspot.com/2017/09/ [Buckinghams]

University of Cincinnati, "The Taft Influence"

The Taft School "Timeline"

Agnes Scott College

Olmsted Brothers

For a master index of all of Bob Foreman's photo-essays, click here.

lovethatbob13@gmail.com

October, 2018

lovethatbob13@gmail.com

October, 2018