These amazing statistic don't lie! With all due modesty, let the record show that between 1967 and 1970, the Taft School Masque and Dagger Society was saved by Theatre People, resulting in an astounding 472.7273% increase in membership-- and there's nothing irrational about that number! (Click any image to enlarge.)

For those unfamiliar, Taft was a preparatory school in Watertown, Connecticut which looked like a castle and whose 400 boy inhabitants were code-named as shown below.

The symbolic and literal explosion occurred in the spring of 1967 when Tommy Strumolo '70 burst onto the Taft stage-- and into the hard-boiled hearts of an all-boy audience-- thereby breaking the "lower mid barrier" which had enslaved his class since the beginning of recorded time. He was 4'-11" tall and weighed eighty-eight pounds.

By 1900, Taft had its own Dramatic Association but no theatre of its own.

All the girls were played by boys. From left to right, boy, boy, boy, boy, boy.

Not the be upstaged, the Chicago Trib boasted two Chicagoans in the same play: Haven La Qua as the male star and T. Cowles as Edith Marsland "who wore a wig of lustrous dark hair and a pink princess gown."

"Charles P. Taft," the Tribune continued, "gave a creditable presentation as Eva Webster in a brown wig and a modest afternoon gown."

Any lingering doubts about his masculinity were dispelled when Charlie (green arrow) played the male lead in the 1913 production of "Going Some" at the Town Hall.

The next year, the old gym, then the new gym, was fitted with a portable stage "with a proscenium wall that stretched across the entire width of the gym and up to the ceiling." Equipped with footlights and three borders, "the whole thing [was] the same as the portable theatre at the Waldorf-Astoria." A.D. Gillette '95, now the drama coach, got the outfit for only $700.

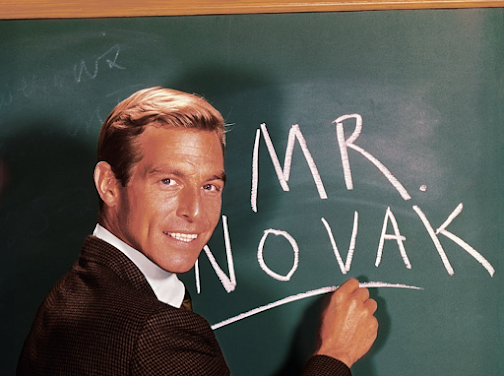

People like Candler tend to create more theatre people, and his best-known creation was James Franciscus, who went on to play "Mr. Novak" on TV. "I always wanted to be an English teacher," grinned Franciscus, "so this show is like killing two birds with one stone." Two of Mr. Novak's 1953 classmates actually were English teachers at Taft, Mr. Geldard and Barc Johnson.

The show was "A Thousand Clowns," the spring play produced under the auspices of the Masque and Dagger Society. The Taft dramatic season also included a fall show (Father's Day) and a winter show (Mother's Day). All three productions pre-empted the regular Saturday night movies shown in Bingham Auditorium.

The director possessed with the courage to cast young Strumolo was Mr. Geldard, shown below demonstrating the proper use of a switchblade in "12 Angry Men," the 1966-67 fall production.

Mr. Geldard was all-Taft, having been reared in Watertown, graduated from Taft, and married to a faculty brat-- the daughter of history teacher Mr. Adams. Geldard's wife was highly regarded by a number of upperclassmen.

Strumolo's bravura performance evoked laughter, and yes, tears, from the jaded Taft audiences. Here he is being embraced by fellow actor and upper mid Bob Sweet, who wouldn't embrace just anyone since his father was deputy to New York City's Mayor Lindsay. Strumolo taught Bob Sweet to be "the best possible Murray Burns."

From left to right, Bob Sweet, "Bubbles" (an artificial girl with electrical flashing breasts), Strumolo, and Susan Brown, a secretary that Mr. Geldard had discovered in the Taft business office. "She lived in Naugatuck and would drive me home from rehearsals in her Saab," recalls Strumolo. "When I was but a small hot-blooded Italian day boy."

Because of Tom Strumolo's athletic prowess, hardly anyone in the school believed him to be a homosexual.

Fifth year senior Eric Ruark complemented Strumolo's performance with his excellent portrayal of "Chuckles the Chipmunk." He bore a passing resemblance to popular comedian Jonathan Winters.

Ruark's agility of movement was due in part to his 6th grade ballroom dancing lessons taught by Miss Coffee in the Hotel Elton in Waterbury where he had been graduated from McTernan, an all-boys K-9 day school, more about which later.

Another photo of Ruark (lower right) shows the two phone booths, located in the basement of the old gym, which provided the only telephonic connection between 400 Taft boys and the outside world. Pre-coeducation, Taft was an insular commune, "the last autocracy" ruled over by Headmaster John Esty, a monarch with absolute power. It was Esty's way or the highway, meaning Route 6.

Tom Strumolo was not the first member of the class of 1970 to trod the Bingham boards. That honor had fallen to John Lee (below), who along with Bill McLean had been cast in the Mother's Day play "Inherit the Wind" (Trial scene). "It was the highlight of my theatrical career," recalls John. "I had one line —to stand up and say 'no!' Also to say 'umbrella umbrella umbrella and soda water syphon soda water syphon.'"

Unfortunately for John Lee, that performance of "Inherit the Wind" (Trial scene) was overshadowed by a performance of "Fracas on Ice" up at the Mays Rink where a bloodbath melee with Choate had occurred that afternoon.

Upper middler Bob Sweet who played the leading role in "Inherit the Wind" (Trial Scene), "A Thousand Clowns," and "12 Angry Men," proved that even an upper mid still wearing braces on his teeth could be a star.

Besides Bob Sweet, the only non-senior in the show was middler Gary Cookson, in his Taft stage debut.

Legalized onstage smoking was offered as an added bonus by the Masque and Dagger, as this photo of "12 Angry Men" attests. Frank Cole on the right.

One could also legally smoke in the tiny dressing rooms before, during, and (most importantly) after a performance. Somewhere in this hot and sweaty photo is Mrs. Lovett-Janison.

For "Clowns" Mr. Geldard engaged the services two Yale grad students, Roger Luken and and Tom Peterson, to design and supervise the construction of the set during afternoon stage crew. Down in the substage, four lower mids including Dave Achelis, identical twins Jeff and Jerry Boak, and young Bob Foreman built a completely new inventory of twelve foot high flats, which were then hauled up through the traps to the stage and anchored in place by stage braces and stage screws. "They showed us how to build standard size reusable flats," recalled Jerry Boak.Identical lower mid twins Jeff and Jerry Boak worked on fourteen productions after "Clowns" in some creative capacity. Curiously, they shared the same birth date with young Bob Foreman.

Afternoon stage crew was wedged in between required Ex and Vespers, except for Wednesday when there was no Ex, thank the Lord.Every aspect of play production at Taft was extra-curricular and voluntary, including the stage plays, afternoon stage crew and permanent stage crew which fell under the jurisdiction of the job program. There were no courses, no teachers, no attendance-taking, and no failing grades. Drama coach Geldard was concerned solely with staging the fall and spring plays and could care less about the maintenance of a dramatic society.

The day-to-day running of the stage was left to five boys, mostly seniors, who were the permanent stage crew. They set the daily 6:00 Vespers, the picture sheet and horn for the weekly movies, and with volunteers from the afternoon stage crew, set the acoustical shell (below, behind pianist George Morgan), a man-sized job consisting of eleven plywood flats ranging from 12 to 18 feet tall and a ceiling which flew into position. When not in use, the piano safely resided in an enclosed "garage" in the prop room stage right. In addition the permanent stage crew serviced two subscription series: Watertown Concert and the Audubon.

Afternoon stage crew played thirty-seventh fiddle to athletics at Taft. There were no afternoon stage crew "lettermen" or lavish end-of-year banquets. In fact, "Inherit the Wind" (Trial scene) was the last club play ever produced at Taft and with it went 30 club points, or the equivalent of 4.28 Head Monitors.

Some lower mids were secretly selected to start the school year early to polish their athletic skills, such as was the case of soccer ace Peter "Pedro" Barrett, who at age 14 was being groomed for the Junior Varsity and called to the school two weeks early, paid in kind with free room and board.

Unlike Barrett, afternoon stage crew boys had to "open cold" and suffer compulsory club soccer without any intensive preparation whatsoever. Boys like young Bob Foreman (circle) who worked on the afternoon stage crew for 12 consecutive terms, had to "participate" two hours daily on the playing field, so close to the auditorium that he could cry.

For straight across the field was a theatre stage designed by James Gamble Rogers and "equipped with every facility for play-production, perhaps the finest building of its kind in the secondary school world," boasted the school catalog entry, memorized by young Bob Foreman. Not to mention the latest Western Electric talking-picture equipment and 527 plush seats.

Where young Bob Foreman (circle) had come from, the "Chapel-Auditorium" had no seats at all, but hard pews instead, unspeakable fluorescent house lights, and nothing at all manufactured by Western Electric.

In Atlanta the stage ceiling was only high enough to snap this photo of the servants being played in blackface.

The permanent stage crew, with the assistance of the volunteers from the afternoon stage crew, were responsible for building the scenery and running the shows.

Unfortunately, in those dark days the afternoon stage crew didn't exactly roll out the welcome wagon for eager lower mids. In fact, there weren't even any mids in the 1967 Masque and Dagger, which photographed like a funeral parlor. "The Society was a coven of noxious, inhospitable trolls bookmarked by a pair of grotesque flaming queens," recalled one former lower mid. No membership lists were posted, so no one knew exactly who was in Masque and Dagger and who wasn't.

The 1966-67 Masque and Dagger membership also seemed to be entirely lacking in the magical qualities one associated with "theatre people," and young Bob Foreman knew what theatre people were, because he had lighted two of them the summer before in a Shakespeare play and had the newspaper clipping to prove it. Left, Miss Collin Wilcox, the slattern in "To Kill a Mockingbird" and her then-husband Geoffrey Horne who had blown up "The Bridge over the River Kwai." "She was the first bitch I ever met," he recalled.

Fortunately there was one human among the Masque and Dagger, sound man Fran Moore '68, and he was willing to teach. "Make yourself indispensable to the school," was his first lesson to young Bob Foreman. "So they can't throw you out." Below, Fran and the new Bingham tape deck with stereo sound-on-sound,

"Work in the projection booth. If Mr. Davis likes you, it can be your permanent job next year," counseled Fran. So in addition to afternoon stage crew, young Bob Foreman began assisting the upperclassman who assisted union projectionist Pops LaFlamme, who had worked in Bingham since the day it opened in 1931. Pops showed the Saturday night and holiday movies on "the latest Western Electric talking-picture equipment." Left, Pops LaFlamme and right, Mr. Davis, who selected the films and directed the club plays.

The past of the Masque and Dagger was vague and shrouded in mystery. In the back of the play-script for "12 Angry Men" was a director's kudo from none other than the Taft School! A previous production, but when? Who was Peter Candler? Why was Taft no longer in the national spotlight? Could Taft ever reach the Promethean heights it had attained?

1967-1968

A slightly older young Bob Foreman returned to Taft for his mid year, having spent the summer as a star-stock apprentice for Atlanta's Theatre Under the Stars in a 5000-seat amphitheatre. He assisted the New York lighting designer, the union guys in the scene shop called him "Young Tom Edison," and among the important theatrical terms he learned that summer were "In one," "lush," "carny trash," and "Go fuck yourself."

That fall of 1967 the lurid historical secrets of Taft dramatics were unlocked when the first school archive appeared in the basement of CPT. Operated by retired history Master Henry Stearns, its most frequent visitor was the inquisitive young Foreman. Every yearbook, Pap, Bulletin, every photograph was there for examination.

Among the historical facts unearthed was that the first dramatically-inclined Taft boy was not an actor, but a stage manager, in the person of A.D. Gillette '95. In the spring of his senior year, he helped to open the new Watertown Town Hall, located to the left of the PO-Drug. Sheridan's "The Rivals," was the opening night play presented in the upstairs theatre by the Watertown Dramatic Association, and the cast included two Taft masters.

As even the least educated Taft student should know, the Headmaster's brother, commencing in 1909, was the President of the United States.

In that very same year, the President's 12-year-old son made nationwide front page headlines for "playing the part of a young woman" on the Taft stage. "His acting won much applause," wrote a California paper.

Taft productions were frequently held over and shared with Watertown in the new 490-seat Community Theatre completed in 1917. The house also included a men's club, a bowling alley, and a women's club downstairs for after-play dancing with real live girls from St. Margaret's School in Waterbury. Later known as the Cameo Theatre,

The new Taft auditorium could have looked like this, originally envisioned as a recital hall, smaller than the proposed school chapel.

But perhaps because Mr. Taft was a Unitarian, the chapel was eliminated entirely and when the $200,000 Bingham Auditorium opened in early 1931, it was a scale version of a Broadway playhouse, with a 30 foot wide proscenium and a stage equally as deep. The wine-colored velour main drape could both travel and fly: for movies, it was drawn; for stage plays, it was flown.

When the auditorium was not in use, the main curtain was kept closed, and a household switch (arrow, center) located on the lobby side of the standing rail enabled school officials to turn on the houselights, a feature used on a daily basis by the admissions department giving tours of the school to prospective candidates. A "lock switch" on the backstage switchboard prevented jokers from turning on the lights during a performance. As a concession to chapel use, each of the 527 chairs were fitted with inconspicuous under-seat hymnal holders, and the hymnals held were utilized every Thursday Vespers.

In Bingham's orchestra pit was one of the first Hammond organs, donated in 1936. The motorized rotating Leslie loudspeakers were concealed behind the filigreed woodwork (and Taft seal) on either side of the proscenium.

The projection room was equipped with two Super Simplex 35mm projectors with Western Electric sound heads and amplifiers and Peerless carbon arc lamphouses updated in 1955 when CinemaScope was installed. To the left of the left balcony exit doors was the non-sync room with turntables for disc reproduction, and two floor up, on the 4th floor CPT plateau, was a room containing the AC-to-DC motor generators sets, necessary for arc lights. The wine velour window drapes were thrown open for this photo; in practice, they were always drawn shut.

In the first known backstage shot were (left to right) the Peter Clark locking rail, the Westinghouse 34-dimmer lighting switchboard, and David Gaines '33. Twelve dimmers each were allocated for floor pockets and the two overhead electric pipes; four dimmers each assigned to footlights and spot receptacles within the footlight trough; and two dimmers controlled the houselights. A telescoping grand master lever facilitated smooth board fades.

If Bingham had one shortcoming, it was that the only provisions for front lighting were the footlights and a Kleigl carbon arc follow spotlight in the booth. So that daily Vespers would not have to be held in the dark, soon after Bingham opened, 30 feet of three-color borderlights (arrow) from the 1917 portable stage were tailed down from the valance border curtain and connected to the unused footlight spots circuits. The fancy oak lectern and the two "Vesper chairs" were designed to match the room.

Drama coach and biology Master Bob Olmstead changed the name of the Dramatic Association to "Masque and Dagger" in 1937, and his directing technique was caught on film which can be seen here. Below the cast and crew of "George Washington Slept Here," 1945.

Mr. Olmstead's final offering was an all-male version of "The Importance of Being Earnest" in 1952, tickets for which were sold by the Boy Scouts for the Red Cross.

Enter Peter Candler, center with pipe, who took over as Taft's drama coach in 1952-3, and everything changed because Candler was a real theatre person. He had spent four summers as press agent at the Monomoy Theatre in Chatham, Mass., and by the time he got to Taft, he was General Manager at the Cape Playhouse in Dennis. Through Dennis, he had New York connections and it was said that Bingham's modern lighting inventory of lekos and fresnels fell off of a friendly Broadway loading dock.

Works of obscurity were not Mr. Candler's cup of tea; he produced hits, well-calculated to draw boys to the Masque and Dagger stage and put asses in seats. In 1957, he authored a detailed description of his operation for the Alumni Bulletin, which can be viewed here.

Summer of 1955, Mr. Candler took Franciscus along with him to Dennis as stage manager, and in 2005 a historical hole was filled when Jane Fonda admitted in her autobiography that she had given up her virginity to Franciscus soon after they met at the playhouse. "The moment I saw him, the complexion of the summer changed," wrote Miss Fonda. Hanoi Jane later delighted Taft-boy audiences with her 1968 film "Barbarella."

Among the hits presented by Candler were "Mr. Roberts," "Ten Little Indians," "The Bat," and in 1955, "12 Angry Men," the original production referenced in the Bob Sweet play-script, left. Candler also operated his own press department, sending out releases to boys' hometown papers, such as the below right, touting Halsey Beemer's contribution to the stage crew for "12 Angry Men."

When Peter Candler produced "12 Angry Men," it was a hot commodity, less than one year after the teleplay had originated live from New York (and not repeated) and two years before the motion picture version, starring Jane Fonda's father.

In 1959, at the peak of his success, Peter Candler was hired away from Taft by Lawrenceville which built a new theatre tailored to his exacting specifications. How often does that happen? His Taft boys bought a full page ad in the yearbook to salute him.

Following the departure of Peter Candler, Headmaster Cruikshank replaced him with a man that no one would hire away. In six short years, the new drama coach and English teacher Toby Allen was able to undo all that Candler had accomplished, and Masque and Dagger membership dwindled from an all time high of 43 (left) to 18, and with Geldard batting cleanup, it hit the all time low of 11 in 1967. Allen's play selections included the crowd-pleasing tragedy "Antigone" and "The Flowering Peach."

While Peter Candler had deified his stagehands, Toby Allen and his minions belittled them. Candler's professional Broadway nomenclature was abandoned in favor of sports lingo: "Chief Electrician" became "Lighting Manager." If the crew was photographed, it was at a blurry distance.

One stage play which never received a production at Taft was Broadway's 1953 "Tea and Sympathy" about a prep school boy suspected of being "a fairy," in part because he was cast in a girl's role in the school play. In the end, the boy is presumably cured of his affliction by a faculty wife who offered tea, sympathy, and more.

All these past events set the stage for "Pantaglieize," Mr. Geldard's fall 1967 play choice, which began the long and tedious succession of faculty-selected plays that no one had ever heard of.

An outstanding addition to the afternoon stage crew for the year 1967-68 was the first of the merry pranksters, lower middler John Spafford. He was a tiny boy, but already a theatre person, complete with a bag of tricks. He would hurl great gobs of wet gelatin at unsuspecting rubes (it didn't stain), and gently poking another sucker in the bum with a broomstick, he would simultaneously start an unseen electric drill right next to his victim's ear. "Never bend over in a theatre" became good advice. Spafford is shown below, between two Boaks and beneath a Small.

For "Pantagleize" Spafford operated one of the two Capitol 1500-watt incandescent follow spots from the balcony rail. "I absolutely loved 'Pantagleize'" gushed Spafford. "And I loved manning the follow-spot."

The first in a series of plays in French "Waiting for Godot" was directed by French master Roland Simon and presented January 25, 1968, and since it played on a Thursday, it did not pre-empt a movie.

Alan Bishop (left) played the Bert Lahr role against Bob Sweet in the part originally played by Tom Ewell, whose son Tate attended Taft. Both Bishop and Sweet had younger brothers in the Masque and Dagger, Greg '73 and Ames '72. "The boys" were played by Larry Lopez '71 (right) in the role originated by Luchino Solito de Solis.

Mother's Day brought another play no one had ever heard of, "The Apollo of Bellac" directed by new boy Latin teacher Mr. Kusterer in which Len Cowan was finally given his first onstage part.

"Bellac" introduced the talents of future Hollywood player Grant Goodeve '70 to the Taft audiences. Like several boys in Masque and Dagger, Goodeve had been trained by Christine Ranft at Waterbury's McTernan, a day school for exceptionally bright boys. Recalls a McTernan classmate, "Grant was not only extraordinarily good-looking, but also a nice and well-liked young man."

Wife of McTernan's Headmaster, Christine Ranft (nee Adams) was a theatre person who had sung on Boston radio as a child and the Boothbay (Maine) Playhouse had been built for her by an ardent admirer. She wrote book, lyrics and music for McTernan's seasonal plays, all of which were musicals performed by the entire school. "Hark, the Angels" was the 1966 offering whose cast included future Masque and Daggers Goodeve, Bruce MacLean, Christopher Walford, and Chip Arnold.

"Hark, the Angels" was a morality play not unlike her other hits, "Take Time for Angels" about a poor little rich boy and "Christmas Comes to Turner's Alley," about a bad gang turned good. Below, the finale of "Hark."

Christine Ranft's production values were extraordinary, judging from this shot of an unknown musical performed on the third floor of McTernan's main building.

Goodeve elected to graduate not from Taft, but from Southbury High where he was voted class vice president, best looking, and nicest smile, honors that would have been denied him in Watertown. Goodeve, below right, in NBC's "Eight is Enough."

Spring brought Geldard's final production "Becket" with a title familiar to moviegoers, Bob Sweet in the Richard Burton role.

Len Cowan was granted a principal role as a Cardinal, seen here with the Pope, Alan Carling. Len would eventually portray an esteemed member of the clergy in real life.

Mr. Strasburger (right), a new boy English Master, composed and played "Gwendolyn's Song" for "Becket." "'Becket' was one of the finest secondary school productions I’ve seen," recalled Strasburger. "Casting Bob Sweet and Glenn Schwetz against each other was sheer genius, and the performance was riveting." Cavorting with Mr, Strasburger are Scott Dunn, Danny Bachicha, Sam Miller, Fred Green, and Mr. Taft.

"Becket" proved to be Mr. Geldard's swan song as he quit Taft in favor of grad school at Stanford, where he could pursue academic theatre.

A lady from Waterbury by the name of Helen Mellon produced a show on the Taft stage in the spring and also several in the summer. During the performance and without warning, Helen Mellon burst into the backstage light booth and shamelessly performed a costume quick-change in the presence of the wide-eyed switchboard operator, namely young Bob Foreman, thereby immediately qualifying herself as a theatre person.

Perhaps the most notable dramatic event of 1967-8 was "The Zoo Story," a 16mm film produced and directed by Bob Sweet in Central Park. This ISP project starred English teachers Dexter Newton and Gene Kusterer, the latter in the William Daniels role.

The year ended with 14 members of Masque and Dagger, an increase of three over the previous year and all due to the class of 1970: middlers Len Cowan, Jerry Boak and young Bob Foreman.

1968-1969

In the fall of 1968, we of the class of 1970 became upper middlers. Because there was no qualified senior, young Bob Foreman was promoted from the projection room to Chief Electrician and this became his permanent job. For his first official act (and with the aid of CPT's central vacuum) he cleaned, serviced, and reactivated the delicious four-color, double-row footlights which had not been used in a decade. They were extremely theatrical.

The footlights were an integral part of the new "Deluxe picture policy," a portion of which is shown below. When one entered Bingham for a movie, the houselights were set very low, popular pre-show music was played, and the curtain changed colors.

Mr. Geldard's replacement was Mr. Kusterer who had selected "The Apollo of Bellac" the year before. When he announced "The Rainmaker" as the fall show, the question was begged, "Why not the far more popular musical version?"

Our entreaties fell upon deaf ears. But for a third rate play at least we had a first rate cast, with adorable senior Colter Rule, lovable faculty brat Debbie Carroll, and winsome Len Cowan, shown below.

"Rainmaker" brought three important new faces to the backstage departments, where lower classmen were now greatly appreciated and welcomed with open arms. Left to right, middlers Chris Walford, Rich Limburg and lower mid Bob Golfman '72. All would excel: Walford as an actor and designer (and Orioco), Limburg as production stage manager, and Golfman as sound man, pit keyboardist, and musical director. Chris Walford was also a McTernan grad and had performed alongside Goodeve in a number of musicals.

By December, a great change had come over Bingham, and even the distant and exalted Headmaster John Esty sat up and took notice-- the fire inspector of the State Police Force "was high in his praise for the condition of the stage."

On Friday, January 31, 1969 the second annual French presentation consisted of two one-acts directed by Roland Simon with the help of Mr. Davis: "La Farce de Maitre Pathelin" and "Pique-Nique," not by William Inge. Newcomers to the stage (and backstage) included Rob Jonker-Fisher and Buck Becker, both '70, and Lee Lochridge and Shan Lawton, both '71, none of whom graduated.

The winter term Mother's Day program included performances by the Concert Band, the Glee Club, and the Oriocos, along the two one-act plays. Mr. Kusterer chose "The Sound of Apples" and "Return Journey."

Apparently Kusterer's highest aim was a royalty-free performance: "Apples" had been a radio play and published only in an obscure collection. "An imaginary episode in the life of Johnny Appleseed" smacked of a 4th grade pageant.

1969-1970

Working directly with Mr. Davis, the boys convinced the school to purchase an Altec A-7 loudspeaker to replace the ancient horn for behind-the-screen motion picture sound, and a much-needed replacement picture sheet was installed as well.

Enormous changes had swept through the school since 1966, as illustrated by the Woodstock Society, left to right, upper mids MacAusland, Bermingham, Snyder, and MDS member Chan Wheeler. Starting with the 1969-1970 school year, the dreaded new boy tie requirement for lower middlers was eliminated, and that year would be the last time coat and tie were required to be worn in class. Lower mids were allowed elaborate stereo systems in their rooms, compulsory church attendance had been abolished, and the Wade, the senior smoking house, was opened to upper mids.

Members of the class of 1970 decided to write and produce an original satirical topical musical revue, and on October 10th, the completed script was typed and mimeographed by Betty Perrone (inset), the divine and efficient secretary to business manager Pratt. The show entitled "Meet Me in My Office at Five O'clock" was scheduled for a winter production and would be the first senior revue produced since "The Queen & I" (1953) and first musical comedy since "Pinafore" (1934).

By way of contrast, over at Lawrenceville former beloved Taft drama coach Peter Candler was slamming boys' asses into seats with a "zany anti-war play" by Catch 22 author Joseph Heller and with Heller's blessing!

And a happy ending with players including Tony Pasqualini '72, who had joined MDS as a lower mid and who became a professional actor.

A publicity shot for the show taken within the sound shell shows Mr. Kusterer directing the placement of a Vesper chair, assisted by Jerry Boak and Dave Addoms '70 and actor Gary Cookson. Cookson's parents were Broadway actors Peter Cookson and Beatrice Straight, so through no fault of his own, Gary was a theatre person.

The only redeeming aspect was the casting of Gary Cookson and three faulty brats, one of whom would later marry Masque and Dagger Rob Clark '72 and produce their own little thespian. Wisely, Kusterer cast the girls as girls.

"Return Journey" was also a royalty-free radio play, but at least it had an author we had heard of. Jeff Boak's setting featured a series of five large wagons, each of which would roll downstage center to play, under the expert stage management of Rich Limburg.

There was something about the "new" Masque and Dagger which attracted lost boys to the stage, such as Steven Erlanger (arrow) who took on the role of narrator with monster sides to learn, a sample below. Erlanger, who had received his dramatic training from McTernan's Christine Ranft, went on to a career as a writer of light comedy.

These two plays brought new talent to the Bingham stage, notably the slightly devilish Barnaby Conrad, below. Owing to his father's celebrity, Barney was a theatre person by osmosis. Indeed, he was later believed to have managed the El Matador nightclub in San Francisco at the age of seven.

An extremely well-received non-Masque and Dagger production that winter was "The Pit of Despair," a sketch performed on the Bingham stage during JA (Wednesday job assembly). "Pit" was a takeoff on "Narcotics: The Pit of Despair," a twenty minute 16mm color film (viewable on the utube) which had been given widespread exposure at private gatherings from 1967 to 1969, including at Taft, and always accompanied by a uniformed state trooper.

Among the many great exchanges in the parody were: "Stanley, I've got something better than Bud." "Better than Bud!!!???" The cast, all '69, included Masque and Daggers Gary Cookson (Dirty Lowhole), Colter Rule (Lomax), and "Oedipus Rock" Shepard, whose father was publisher of Look magazine. Alan Denzer (Baby Face McGuire) was himself a victim of Taft's first actual pusher the year before. "I got in trouble with 'Mary Jane,'" read his annual blurb. "She hid in my suitcase."

By far the most popular use of Bingham were the Saturday night and holiday movies selected by Mr. Davis strictly for their entertainment value. The titles were not announced in advance, so at curtain time at least, the houses were full and bubbling with boyish excitement. And unlike Vespers and JA where the seating assignments were alphabetical by class, the films were a free for all. "After the movie starts, students may remove coats and loosen ties," instructed the Student Handbook, which can be viewed here.

The best-received Bingham pictures were those which included Playboy fold-out plots in Technicolor, magnified to fit Taft's 28 foot wide CinemaScope picture sheet, in this imaginary western.

The students found a tattered copy of the original Masque and Dagger Constitution and had Betty Perrone type a new version for ratification. Years ago, it turned out, the boys had a voice in the choice of plays but in a strange reversal, the boy's civil liberties which had been granted in the 30's and nurtured in the 50's had been rescinded in the 1960's by "liberal" faculty members.

With all these facts in hand, drama coach Kusterer opted for a play that absolutely no one would enjoy-- or attend: "The Journey of the Fifth Horse." At the same time, he announced that he would not be returning to Taft the next year.

His bizarre and obnoxious choice of play unleashed a fury among the boys, and the stage crew threatened to go on strike. One week after "Fifth Horse" a letter to the editor-- an ultimatum-- appeared in the Pap, which ended "Unless the director-hirers of the administration make [next year's] director aware of our feelings [about play selection], the lights will not shine on the Taft stage."

The head "director-hirer" himself, Headmaster John Esty (left) read the letter and became extremely angry. En route to lunch, the Headmaster grabbed young Foreman by the elbow and instructed him to "meet me in my office at five o'clock." In the subsequent meeting, the Headmaster vented his rage and threatened to shut down the stage for good. There were two eventual outcomes: (1) The Headmaster did not shut down the stage and (2) young Foreman had a play title.

One of the very few productive results of "Fifth Horse" was the arrival of lower middler Bill Waldron (circle) backstage. Unlike most crew boys, Waldron was a closet athlete, shown below as the only underclassman on the club "A League" hockey team, otherwise comprised of all upper mids. Billy was a merry prankster.

"Fifth Horse" also marked the first time in a decade that the Masque & Dagger membership was listed in the program book. The membership had swelled to 42, and most importantly that number included underclassmen: two lower mids and eleven mids, several of them future theatre people.

Of course, there would be no theatre people at Taft without a capable casting director-- in this case, the Director of Admissions Joe Cunningham (left), shown making change for lower mid Rick Schnier '73.

1969-1970

During the summer, Len Cowan refined his craft with a real live girl at the Dorset Playhouse in Vermont.

Young Foreman utilized the printing press at his summer stock job to make calling cards for the permanent stage crew, including four seniors, two of them twins, and one upper mid, Rich Limburg. The inmates were now officially running the asylum.

The new crew immediately continued improvements to the physical plant. The purchase of 12 additional six inch fresnels (at Times Square Lighting) provided an excellent downstage light source when tailed down from the valance (arrow), despite the fact that they had to be removed after each production and the valance borderlight restored. (It wasn't until the mid-1960's that permanent balcony rail

lights had been installed, consisting of six 8" 1K Capitol lekos and one model 901 1500 watt follow spotlight per side, all fed from circuits tapped off of the existing

stage floor pockets.)

Circumventing the dramatic coach and going directly to the school's business manager allowed for the purchase of a new 80 foot sky-blue cyclorama and replacemen gold and black velour travelers. Below, business manager Captain Pratt, who also provided his daughters when required.

The original Kliegl connector strip, shown in this photo with drama coach Olmstead, had been removed in the mid-50's for reasons unknown. In the fall of 1969, when it was discovered in one of the school's barns, the boys hoisted it on their shoulders, walked it down the hill to Bingham, and rehung it on the first electric. The strip was a great boon because it effectively eliminated the need for stage cable at that lighting position.

Working directly with Mr. Davis, the boys convinced the school to purchase an Altec A-7 loudspeaker to replace the ancient horn for behind-the-screen motion picture sound, and a much-needed replacement picture sheet was installed as well.

A number of exciting events preceded the annual Father's Day stage production in November. The first was an invitation to Jeff Boak by neighboring girls' school St. Mag's to star in their October play, Ionesco's "The Lesson." In the play, Jeff's character kills his co-star "with a spectacular thrust of an invisible knife." Following the performance, Jeff's co-star "invited herself to Taft" and in Bingham Auditorium, she proceeded to try to rob Jeffrey of his virginity.

Directly on the heels of Jeff Boak's success story, both Boak twins were thrust into the national spotlight via a command appearance on "The David Frost Show" which was videotaped in the summer and telecast on Monday morning, October 6th. Unfortunately, class attendance requirements conflicted with the morning broadcast, and the boys were not allowed to view themselves.The strange events of fall term 1969 began to unfold when the rumor circulated that Paul McCartney was dead, and every corridor echoed with the White Album and "Turn me on, dead man," courtesy of WDRC-AM and WDRC-FM, Hartford.

Right about that time, Bill Waldron (left) and three fellow pranksters (and future MDS crew members) received a nocturnal visit from a stranger at their digs in Congdon House. The friendly stranger, who introduced himself as a Taft graduate, lit up a cigarette and because these mids were merry pranksters, they could not help but illegally join in.

A good smoke was had by all, but the next morning the stranger turned in the boys to the Dean, and illegal smoking meant a suspension. The mysterious stranger turned out to be a former Head Monitor who had graduated three years prior. Due to these "incredibly unusual circumstances," the mids were warned but went unpunished. One prankster asked, "What kind of human being does this?"

A good smoke was had by all, but the next morning the stranger turned in the boys to the Dean, and illegal smoking meant a suspension. The mysterious stranger turned out to be a former Head Monitor who had graduated three years prior. Due to these "incredibly unusual circumstances," the mids were warned but went unpunished. One prankster asked, "What kind of human being does this?"

On Saturday, the first of November, Dean of Studies and English Master Bill Sullivan dropped dead of a stroke while watching his son win a football game at Groton. The senior revue sketch which portrayed Mr. Sullivan as Superman was cut from the show.

The new faculty drama coach was named Mr. Armstrong, and he looked like a lower mid. Naturally, his fall play choice was another dog, a royalty-free 16th century clinker, Machiavelli's "The Mandrake." But having extracted from Mr. Armstrong a promise that he would keep his hands off the senior revue, that the spring show would be a musical, and that the winter show would be student-selected and student-directed, the MDS bit the bullet and produced his "Mandrake" to an acre of empty seats.A flock of outstanding new crew members made their debut, including upper middlers Scott Allison, Mike Barry, Parker Griffin, Tom Gronauer, Steve Sutton, and Mike Watkins; mids Christopher Boynton, Wyn Evans, Peter Miller, and Ames Sweet; and lower mids Louis Bernstein and Jeff Gronauer.

"The Mandrake" suddenly became ancient history when during the strike following the Saturday performance middler Bill Waldron '72 fell through the stage traps to his death. "I was the stage manager for 'The Mandrake,'" wrote Dave Addoms, "and Billy was my assistant. During the show Billy sat in the floor with me and we made faces at the actors and had a good laugh." To learn more about the Bill Waldron story, click here.

In the aftermath, a flock of Bill's Congdon House classmates decided to join the stage crew, including Keith Fell, Jeff Lord, Bruce Maclean, Kennie Saverin, Jon Turak, and Mike Castillo, J.G. Taft, and Peter Byerly, shown below. One boy commented, "I certainly felt pretty confused for much of my time at Taft. However, MDS/Bingham was a very interesting place to be confused in." In a year, Golfman, Taft, and Byerly would be running the stage.

Billy Waldron had been very excited about "Meet me in my Office at Five O'clock," and so it was dedicated to him. In a stroke of someone's genius, Len Cowan (right) was named stage director and joined the creative team with young Bob Foreman (right) and revue book writer Had Cluett, center.

The shows's score marked the first time show tunes were ever heard on the Taft stage, with parody lyrics set to the music. The talented pianist Mike McQuilken, who could both sight-read and play by ear, was named musical director, and joining Mike in the pit was senior Danny Bachicha on trumpet, lower mid Greg Bishop on percussion, and teacher Mr. Russell on string bass. The overture was a Broadway version of the Alma Mater.MDS member Steve Erlanger, also editor of the Pap, gave the show terrific press coverage, starting with the announcement on December 6th that the show would play on Sunday night, January 18th. The show was duly cast, and at the conclusion of Christmas break on January 6th, the show went into rehearsal.

Headmaster John Esty must have missed that article, because at dinner on dress rehearsal day, Mr. Esty once again elbowed young Bob Foreman saying "I want a script on my desk right after dinner or there won't be any show tomorrow." Foreman complied.

Naturally this unexpected turn of events threw everyone involved into a high state of nerves, including director Len Cowan.

Naturally this unexpected turn of events threw everyone involved into a high state of nerves, including director Len Cowan.

Perhaps because the script did not contain stage directions, Mr. Esty did not exercise prior restraint, and the show went on as scheduled.

If stage directions had been included, the Headmaster would have seen that in director Cowan's hilarious production, Gordon Hard's Esty (below) made his singing entrance while riding a bicycle across the stage, draped in a cape and crowned by Burger King. This sight gag brought down the house and set the tone for the rest of the show.

Preceding the revue and warming the fire curtain were Nicholas Biddle and the Loco-Focos singing "The Battle of New Orleans" and more.

The revue contained a series of takeoffs of TV show parodies, such as "I Love Trudy," an homage to the school dietitian and her imagined love affair with the Dean of Students. Below, Dean Oscarson (right) and Trudy Gillespie (left) with their counterparts Chip Arnold '71 and Scott Dunn '70 (center) singing "Oh Happy We" from "Candide." Chip Arnold was McTernan-trained.

The high point of the evening was the Kitchenette Ballet, brilliantly staged by Cowan, which brought the inhabitants of the Wombatorium right down into the aisles. "We were made for better things than this," complained Emma Feelya, danced by Bill McLean, left. Ned Whitlock and Chan Wheeler were upper mids.

The segments of the revue were threaded together by "Prep School Place," an In One soap opera whose announcer (young Bob Foreman) was found to be an escaped lunatic at the finale. He was removed from the stage by nurse Giv Goodspeed '70 and Peter Fricker '71 as Dr. Bassford.

The extremely appreciative audience included a former member of the class of 1970, Ralph Schusler, who had been tossed the year before when he was spied smoking a cigarette through a window. Ralph was expelled and matriculated to Loomis. Another special guest, former Master Frank Strasburger, drove up from Gilman in Baltimore to see the show and conveyed Ralph back to Loomis before his illegal permission was discovered.

"Meet Me" was hailed as the first productive use of a Sunday night in the history of the school. Below, Headmaster Esty on the cover of the program book.

All told, 70 boys worked in the cast, stage crew, or front-of-house for "Meet Me," including 37 newcomers. "Meet Me" was the first MDS show to be audio recorded.

Riding on that crest of success, a month later and for the first time, the Mother's Day one-act was chosen by the MDS and entrusted to a student director. Dave Addoms '70 was director, Mike McQuilken was back in the pit, Jeff Boak stage managed, and his twin brother designed the set.

The other twins, Robert and Gordon Hard, whose father was a senior editor at Reader's Digest, proudly appeared onstage in drag as Daisy and Mrs. Abigail McScrew respectively, along with Jack Burton '71 and Trennie Walker '70, shown in this rehearsal shot. Nine newcomers joined the thespic ranks, including two lower mids and five mids.

The professional guidance and craftsmanship of Yale designer Roger Luken was still in evidence in the setting for "The Great Western Melodrama" which was built from the stock flats that the crew had constructed for "A Thousand Clowns" in 1967. Below, designer Jerry Boak's painting elevation for the set which also utilized a stock flown ceiling.Young Bob Foreman and Dave Addoms took a mid-winter break from Taft production and trained it down to the City to witness a stage show at Radio City Music Hall from backstage, where they watched (and smoked) right next to the control board operator. So impressive was the experience that Foreman wrote of it fifty years later in two articles, about the stage elevators and the stage electrics.

March brought the third French play, Ionesco's "Les Chaises" featuring an elderly couple, Jerry Boak, and 35 chairs. A semi-circular set was constructed from stock flattage, and the lighting was designed by middler Chris Boynton.

"The Threepenny Opera" (3PO) was selected by Mr. Armstrong for the first spring musical and was publicized in pre-recorded announcements from "the voice of the Masque and Dagger" as featuring girls from St. Margaret's as "various prostitutes." Mack the Knife was portrayed by Len Cowan in a dazzling performance.

Another top-notch musical director was engaged for 3PO in the person of Tom Castle '70, who played both piano and the pit Hammond for the show, assisted by senior Sandy Simmons on percussion and banjo.

Jerry Boak's platform set and the use of the valance electric can be seen in the 3PO light plot. A ramp extended out over a portion of the orchestra pit, interrupted with a gap to allow for the fire curtain.

Len Cowan, center, enjoys some excellent legal onstage smoking amongst the whores "recruited from Leo's Confectionery," according to one prankster. 3PO was the first MDS production to be videotaped, albeit in monochrome.

All told, more than 100 boys had participated in MDS in 1969-70, or one-quarter of the school. According to the "Threepenny" program book, MDS membership had climbed to 63, the highest ever, including the captain of the Varsity football team, the editor of the Papyrus, the editor of the Annual, and the Head Monitor.

The 1970 yearbook wrote: "This year, the director agreed with the four officers that MDS is a student club, and the students should therefore have something to say, rather than leaving all decisions up to the dictator, or director.

Because young Bob Foreman (right) had heeded Fran Moore's advice and made himself indispensable to the the school, Headmaster Esty (left) allowed him to graduate.

Foreman was even given a prize for his good work, a book written by the very man who had arranged for Foreman and Addoms to visit Radio City and watch the show from backstage.

A new prize was given for the first time on May 23, 1970, the Bill Waldron Memorial, "awarded annually to a member of the student body, with preference to a member of the middle class, who through his interest in the stage has contributed the most to the technical aspects of drama at Taft, as exemplified by Bill Waldron '72." A plaque was mounted in the Bingham lobby, and the first recipient was Peter Byerly '72, left.

The legacy left behind by the new Masque and Dagger began with the fall 1970 Alumni Bulletin, which for the first time dedicated a cover to a stage play and included the a five-page spread about the MDS. Actors Nelson Denis and Keith Reynolds are seen below, lighting design by J.G. Taft '72 and photo by middler Brad Joblin.

That theatre had become a part of the school was evidenced by the Pap of May 21, 1971 which gave over an entire page to an MDS feature story.

The 1970-71 MDS membership represented a 472.72727272.3% increase over that of 1967, all before co-education.

Most importantly, the spring musical became a tradition.

###

Dedicated to Bruce Maclean (1954-2025).

To view the program books, click here.

Special thanks to Louis Bernstein for back issues of the Pap; Jeff Boak for program books; Jerry Boak for drawings; and Francis Martin of the Mattatuck Museum for McTernan School material.

Thanks to Peter Barrett, Joanne Barthelmess of the Watertown History Museum, Pooh Bartlett, Peter Byerly, Len Cowan, Steve Erlanger, Fred Forsman, Jeff Gronauer, Tom Gronauer, John Lee, Bruce Maclean, Dave Marshall, Peter Miller, Connecticut historian Charles Monagan, Tony Pasqualini, Mark Robinson, Taylor Rockwell, Eric Ruark, Colter Rule, John Spafford, Tom Strumolo, Steve Sutton, Monte Thompson, Luci Waldron, Chris Walford, Jock Yellott, and Michael Zande.

For an index of other Taft School articles, click here.

For a master index of all of Bob Foreman's photo-essays, click here.

April 29, 2024

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20TOM%20STRUMOLO.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20GELDARD.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BOB%20SWEET.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.JPG)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20ERIC%20RUARK.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JOHN%20LEE.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20PETER%20COOKSON.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20FRANK%20COLE.png)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20ROGER%20LUKEN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JEFF%20BOAK%20&%20JERRY%20BOAK.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20GEORGE%20MORGAN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20PETER%20BARRETT.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BOB%20FOREMAN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BLACKFACE.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20COLLIN%20WILCOX.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20FRAN%20MOORE.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20RICHARD%20DAVIS%20&%20POPS%20LAFLAMME.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20HENRY%20STEARNS.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20WATERTOWN%20TOWN%20HALL.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20HORACE%20DUTTON%20TAFT.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20DAVID%20GAINES.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20OSCAR%20WILDE.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BLACKFACE.JPG)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20PETER%20CANDLER.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20PETER%20CANDLER.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.png)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20HALSEY%20BEEMER.JPG)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20PETER%20CANDLER.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20TO%20STRUMOLO.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JEFF%20BOAK%20&%20JERRY%20BOAK.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20LEN%20COWAN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JOHN%20SPAFFORD.jpg)

%20crop.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20ROLAND%20SIMON.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20ALAN%20BISHOP%20&%20GREG%20BISHOP%20&%20AMES%20SWEET.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20GRANT%20GOODEVE.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20CHRISTINE%20RANFT%20&%20MCTERNAN%20SCHOOL.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20GRANT%20GOODEVE.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20LEN%20COWAN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20NELSON%20MERRELL.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20DAVE%20ADDOMS.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20SAM%20MILLER.jpg)

A%20GELDARD.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20HELEN%20MELLON.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20DEXTER%20NEWTON.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20FOOTLIGHTS.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20FOOTLIGHTS.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20DEBBIE%20CARROLL%20&%20COLTER%20RULE.jpg)

%201968%2011%2001%20RAINMAKER%20DONALDSON%20GODEVE.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20GRANT%20GOODEVE.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20CHRIS%20WALFORD%20&%20RICH%20LIMBURG%20&%20BOB%20GOLFMAN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BOB%20FOREMAN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JERRY%20BOAK%20&%20DAVE%20ADDOMS.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20MARY%20CURRIE.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20STEVEN%20ERLANGER.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BARNEY%20CONRAD.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.JPG)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20COLTER%20RULE%20&%20ROCKY%20SHEPARD%20&%20ALAN%20DENZER.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BILL%20WALDRON.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20LEN%20COWAN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.JPG)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20KLIEGL%20CONNECTOR%20STRIP.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%201970%20woodstock%20Rob%20Snyder%20Chan%20Wheeler%20%20Pete%20MacAusland%20Biff%20Bermingham.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JEFF%20BOAK%20add.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JERRY%20BOAK.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BETTY%20PERRONE.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BILL%20MACLEAN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BILL%20SULLIVAN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20CHRIS%20BOYNTON%20&%20PARKER%20GRIFFIN%20&%20PETER%20MILLER.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20PETER%20BYERLY%20&%20JOHN%20TAFT%20&%20MIKE%20CASTILLO%20&%20BOB%20GOLFMAN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20HAD%20CLUETT.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20MIKE%20MCQUILKEN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JOHN%20ESTY%20&%20MEET%20ME%20IN%20MY%20OFFICE%20AT%20FIVE%20O'CLOCK.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20GORDON%20HARD.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20LOCO%20FOCOS%20LETTER.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20CHIP%20ARNOLD%20&%20SCOTT%20DUNN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20NED%20WHITLOCK%20&%20CHAN%20WHEELER.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BOB%20FOREMAN%20&%20GIV%20GOODSPEED%20&%20PETER%20FRICKER.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20RALPH%20SCHUSLER%20&%20VESPERS.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JOHN%20ESTY%20&%20MEET%20ME%20IN%20MY%20OFFICE%20AT%20FIVE%20O'CLOCK.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20TRENNIE%20WALKER%20&%20JACK%20BURTON.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JERRY%20BOAK.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20DAVE%20ADDOMS.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20TOM%20CASTLE.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20LEN%20COWAN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20DEBBIE%20CARROLL%20&%20BARBARA%20LISTON.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BEN%20HALL.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20PETER%20BYERLY.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20BRAD%20JOBLIN.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JG%20TAFT.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&.jpg)

%20TAFT%20SCHOOL%20&%20BINGHAM%20AUDITORIUM%20&%20MASQUE%20AND%20DAGGER%20&%20JG%20TAFT.jpg)